An Open Letter to Open-World Video Games (Part 1)

One closeted video gamers confessions about the genre he just can't quit

Dear open-world video games,

I love and hate you. What follows is an honest attempt to explain why.

Part 1: The Good

The pirate’s life for me

I never owned a video game console until adulthood. In the fall of 2014, feeling frustrated with my job, I ordered a PlayStation 4. Nearly a decade later, I suspect that young men who are frustrated with their jobs account for a significant portion of PlayStation’s annual revenue.

My first open-world game was Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag, set in the golden age of Caribbean piracy. After a few story missions, I got a sailboat, map, and spyglass and was told “good luck and have fun with all the stabbing.'“ All open-world games follow this formula: after initial tutorials, they release you onto a vast map with various icons, objectives, and side quests to tackle in any order.

Sailing my pirate ship across the Caribbean, I explored islands, sank ships, and raided forts instead of completing the main story missions. These side activities were thrilling and provided cash to upgrade my pistols and cannons for taking on tougher opponents and earning even more treasure.

On the rooftop of a sugar plantation, I parried a British officer’s bayonet with my sword, finishing him off with a dagger to the throat. Picking up his musket, I confidently dispatched the guard running to sound the alarm, feeling like Daniel Day Lewis in The Last of the Mohicans. “That was awesome,” I said giddily, swooping down from the roof to collect some more loot.

This fantasy was immersive and intoxicating. When sailing my ship at full speed, my crew sang sea shanties, a sense of possibility hovering on the horizon next to a gorgeous sunset. While by day I was an insecure 24-year-old event planner unhappy with his job and uncertain about his relationship, at night I was a successful pirate. Even though I never finished the story, I couldn’t have asked for more from any video game.

Red Dead respite from reality

In the spring of 2020, I began playing Red Dead Redemption 2, an engrossing journey into the twilight of the American Wild West. It was the perfect game for that moment in time. Open-world games are practically designed for pandemics, a mental vaccination against boredom and claustrophobia. Even when confined to an apartment with the outside world in chaos, they provide you with an alluring escape hatch.

While Red Dead’s story and voice acting were excellent, the real selling point was the vast open-world. There, I found beautifully designed and exquisitely rendered landscapes, from spooky Bayous to desolate mountains, with pine forests, cactus-studded deserts, and granite valleys in between. Every area I entered had unique plants and animals that I could hunt, fish, and gather at my leisure, underneath photorealistic skies complete with picturesque sunsets and real weather patterns. I often rode my horse into the mountains just to explore, go hunting, or spend a night beneath the stars.

Alexis abhorred gunplay, so when she had the controller, she’d ride into town, get a haircut, buy new outfits and apples for our horse, and pet every dog she could find. She christened our frequent Red Dead sessions as “Clip Clop Horsey Fun Time.” These adventures felt as integral to surviving early COVID as anything the government did.

As California burned and our president offered us little more than rakes and blame, I escaped into Red Dead's mountains, far away from Trump, COVID, and wildfires. I intentionally progressed through the game slowly, spending as much time in the open-world as humanly possible. While my stint as a pirate offered little more than escapist hedonism, in the captivating landscapes of the old West I was astounded to find stillness, awe, and peace.

Horizon zero regrets

With my wild west adventures behind me, I had to face a world where I was about to turn 30 in one of the least festive environments imaginable. Faced with this overwhelming prospect, I started playing Horizon Zero Dawn. In this world, I was Aloy, a red-headed hunter and outcast in a post-apocalyptic landscape dominated by primal tribes and robot dinosaurs. Since Aloy was a ginger, I christened this game “red head redemption.”

Horizon Zero Dawn exemplified the strengths of the kind of truly immersive hero’s journey that only a video game can deliver. Exploring this enchanting world, Aloy and I uncovered the connection between my perilous present and Aloy's haunting future. By fighting robot dinosaurs and befriending new allies, I grew from a naive youth to a fierce warrior and savior of my people. My journey as Aloy illuminated themes of hope, environmentalism, and the choice between tribalism and unity in a world in crisis.

It was the summer of 2020. Everyone on the internet was screaming at each other about whether racism was real, whether COVID was real, whether Trump, Biden, or no one could do anything about any of it. As Reilly I had to contend with all this. As Aloy, I did not. I relished this alter-ego, at one point joking to my therapist that after hours of content marketing I’d clock out as Reilly and clock right back in as Aloy. She wouldn’t introduce the concept of auto emotional regulation via dissociative behaviors for another year, so I had some gloriously indulgent gaming to do until then.

Every time I felled a robot dinosaur with my bow, I’d take a moment to collect its scrap parts, which could be sold to merchants or crafted into new weapons and ammunition. Every mini victory fueled my desire and ability to seek out new ones. It was a clever micro economic loop that was as satisfying as it was addictive.

One day, a diabolical combination of wildfire smoke and a COVID surge meant that opening our windows, much less going outside was out of the question for the whole weekend. So I holed up in our living room and played Horizon for 12 hours straight. By the end of this bender I’d slaughtered an ungodly number of machines and upgraded all of my weapons. Yet, I suddenly felt the youthful glee of this unchecked indulgence turn into another feeling entirely—a dizzying, disorienting emptiness that left me wondering what my life was becoming. Then, I picked my controller back up and set these thoughts aside for another day. Like Aloy, maybe I was just making the best of a bad situation by scavenging what joy and utility I could find in my desolated surroundings.

Stylish samurai salvation

By the winter of 2020, little positivity, power, or motivation remained in my world outside of video games. I was stuck in a 600 square foot apartment indefinitely. Meanwhile, our landlord was trying to sell the building. The only thing more on fire than the Sierra Nevada mountains was the Bay Area real estate market, and the only thing surging more than housing prices was another COVID wave. So, while sheltering in the only space that felt safe, we kept hearing knocks on our door as masked realtors tried to show affluent couples our cramped living quarters so everyone but us could improve their living situation and finances during a global pandemic. Outside of our apartment, Trump appeared mortally wounded yet more dangerous than ever. Despite decisively losing the most stressful election of my life he just wouldn’t go away, hovering menacingly like the villain in a slasher movie.

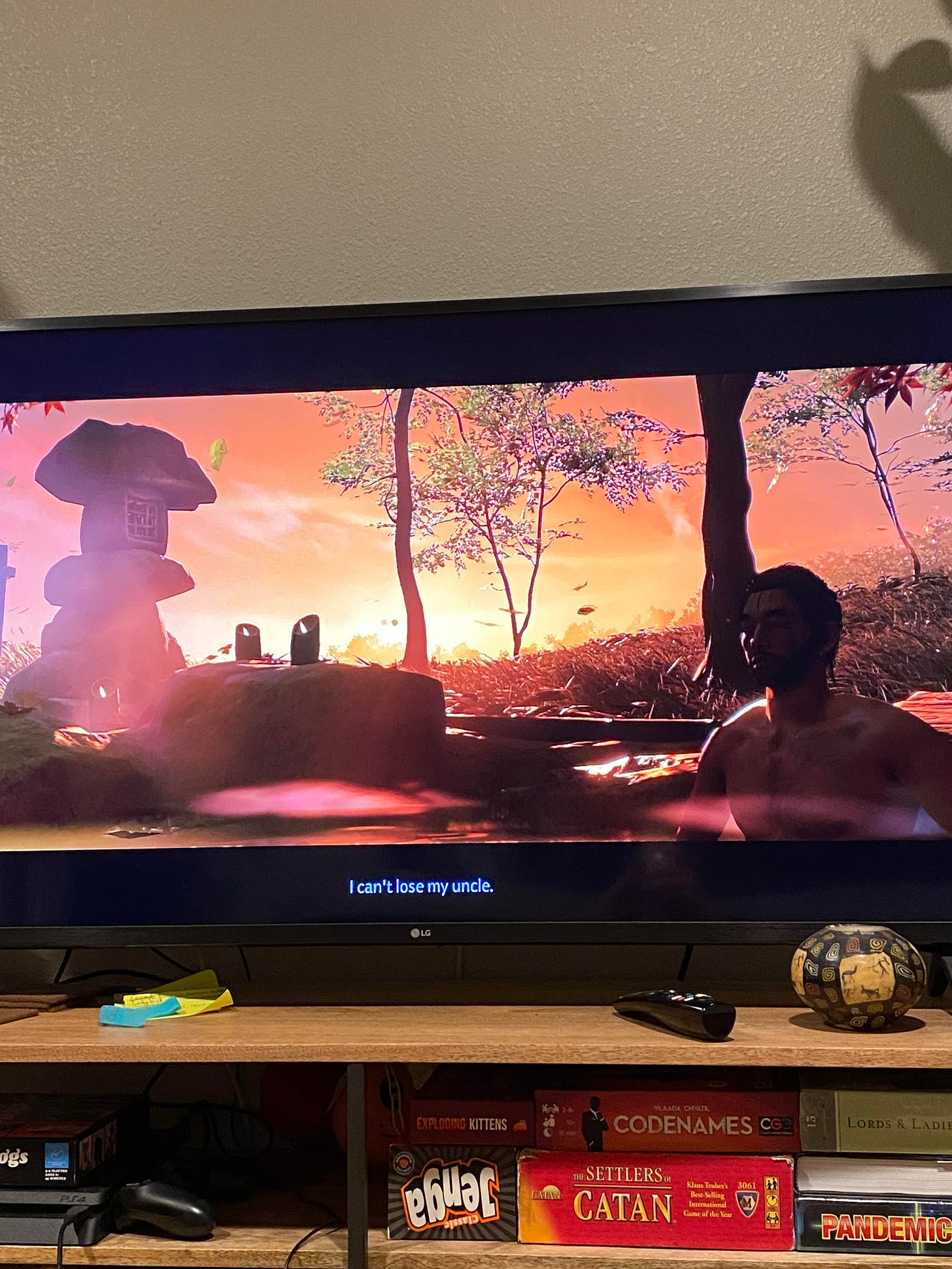

With this bleak backdrop, I procrastinated finishing the story of Horizon Zero Dawn even longer than I had with Red Dead. However, by New Year’s Eve I needed a new fix. So, after several glasses of champagne in our tiny, soon-to-be-sold apartment, I decided a journey to medieval Japan was exactly what Dr. Fauci ordered. Hello, Ghost of Tsushima.

Transported to an island halfway between Japan and South Korea, I became Jin Sakai, a samurai tasked with defending his home from the Mongol invasion of 1274. Yet while the game was marketed around the power fantasy of being a samurai moonlighting as a ninja, the experience of playing it was nearly as sobering as the news cycle.

In my initial excursions as Jin I was a fragile, uncoordinated mess with the durability of a Pringle in combat. I stumbled through early missions, looking about as stealthy and graceful as a bumblebee. The enemy soldiers would spot and swarm me, tearing me to pieces as my puny health bar met the business end of their unblockable spear attacks. It was maddening.

One evening, I found myself on the edge of tears from the frustration of this game. In a world where literally everything felt hard and scary, somehow my precious escapism had become stressful, too. In response, Alexis volunteered to make dinner and told me to lower the difficulty setting until I improved my skills. Here was a rare corner of life where I quite literally didn’t have to play on hard mode.

She was right. The game was more fun when it wasn’t infuriatingly difficult, and having more fun let me keep going long enough to unlock all of the different stances necessary to fight the different classes of bad guys. I also discovered new weapons like throwing stars and smoke bombs, as well as bows, a blow gun, and grenades, all of which gave me new ways to infiltrate strongholds and defeat enemies, empowering me to take on more of the map and story.

Getting humbled early on hadn’t broken me. It just doubled my resolve to train harder. I knew I could defeat my enemy’s overwhelming numbers through cunning, precision, and persistence. This made even mundane tasks felt momentously important. When a sake brewer flagged me down on the side of the road, I didn’t view his side quest as a chore but a chance to grow and prove my worth as a friendly neighborhood samurai.

Ghost of Tsushima taught me many important lessons, starting with how the best part of an open-world game is also the messiest: the middle act. During the beginning of your journey you’re a newly born calf and by the end you’re a demi-god, both equally unflattering to the difficulty curve, but the thrilling balance in the middle is oh so sweet. This is when the story has grabbed you and you’re powerful enough to be confident, but vulnerable enough to be cautious. When your capabilities are limited, the constraint forces you to be thoughtful and creative. This makes each victory feel earned and satisfying.

In an era defined by uncertainty and isolation, where everything else felt daunting, Tsushima’s enthralling yet perilous landscape quickly became my refuge. The challenges I was overcoming as Jin Sakai gave me some semblance of stability, mastery, and purpose amid the psychological turbulence of that first COVID winter. Each mission completed and skill unlocked wasn't just about progressing in the game; it was about reclaiming a sense of agency in chaos, remembering that even in the toughest times, we can always find ways to keep moving forward.

While I had no idea what 2021 held for my apartment, my job, or the pandemic, on Tsushima I had a clear mission. My uncle was held captive in a castle to the North. Our farms and villages were swarming with more unruly invaders than the Capitol on January 6th. Tsushima needed me and I needed Tsushima. Stopping wasn’t an option. So, I kept playing.

To be continued in part 2…

Know someone that would enjoy this post?

Be sure to subscribe so you’re the first to know about new articles!

What’s your relationship to video games like?

I have played video games my whole life, but almost exclusively single-player experiences, usually deep and long RPGs (where "size" and "time to finish" are universally presented as positive features, which....). I have always had the relationship with gaming that I have with giant novels or series (Game of Thrones, Wheel of Time) where it's a fully personal immersion into another universe that I learn in great detail. Final Fantasy, Chrono Trigger, Pokemon, and Morrowind were my early and forever introductions and loves here. This also scratches the project manager side of my brain in terms of managing inventories and maximizing leveling.

But that story and immersion needs to respect me and my time too- when it becomes checklists, icons, tasks to do that don't feed either the written or emergent story that I am experiencing.... I'll leave it to your part 2.

I am always fascinated by the overall term of "gaming" or "gamer" and how I'm essentially interacting with a completely different piece of art in an opposite way than someone that, e.g., plays an online loot shooter nightly with friends, or logs onto a competitive sport game to play competitive matches online.