Let's Clear the Air

An unfiltered account of my relationship with air purifiers

My first date with Alexis, a standup comedy show on October 13, 2017, was delightful except for one thing: the air quality was horrendous.

The smoke came from the Napa fires, the first to hit home for me.

Growing up in Berkeley, I heard my friends' parents mention the 1991 Oakland Hills fires, but they felt distant. For me, the most lasting impact of that fire was a computer game. After game designer Will Wright lost his house in the fires, the experience of rebuilding his life inspired him to create The Sims. He also added recovering from a fire as a playable scenario in 1993’s SimCity 2000.

Until 2017, wildfires had been a theoretical threat. They were something I'd occasionally see on the news in Southern California and react to with the same distant concern as a hurricane in Florida or a tornado in Texas. By the end of the Napa fires, the threat was on my doorstep: 44 people were dead, 90,000 had been displaced, and nearly a quarter of a million acres had burned. As grim as that fall was, I was unaware of two crucial facts.

The first was that 2017 was just a warmup for 2018, the deadliest year of wildfires in California’s history. The second was that wildfires would become a part of every summer and fall in the Bay Area for the foreseeable future.

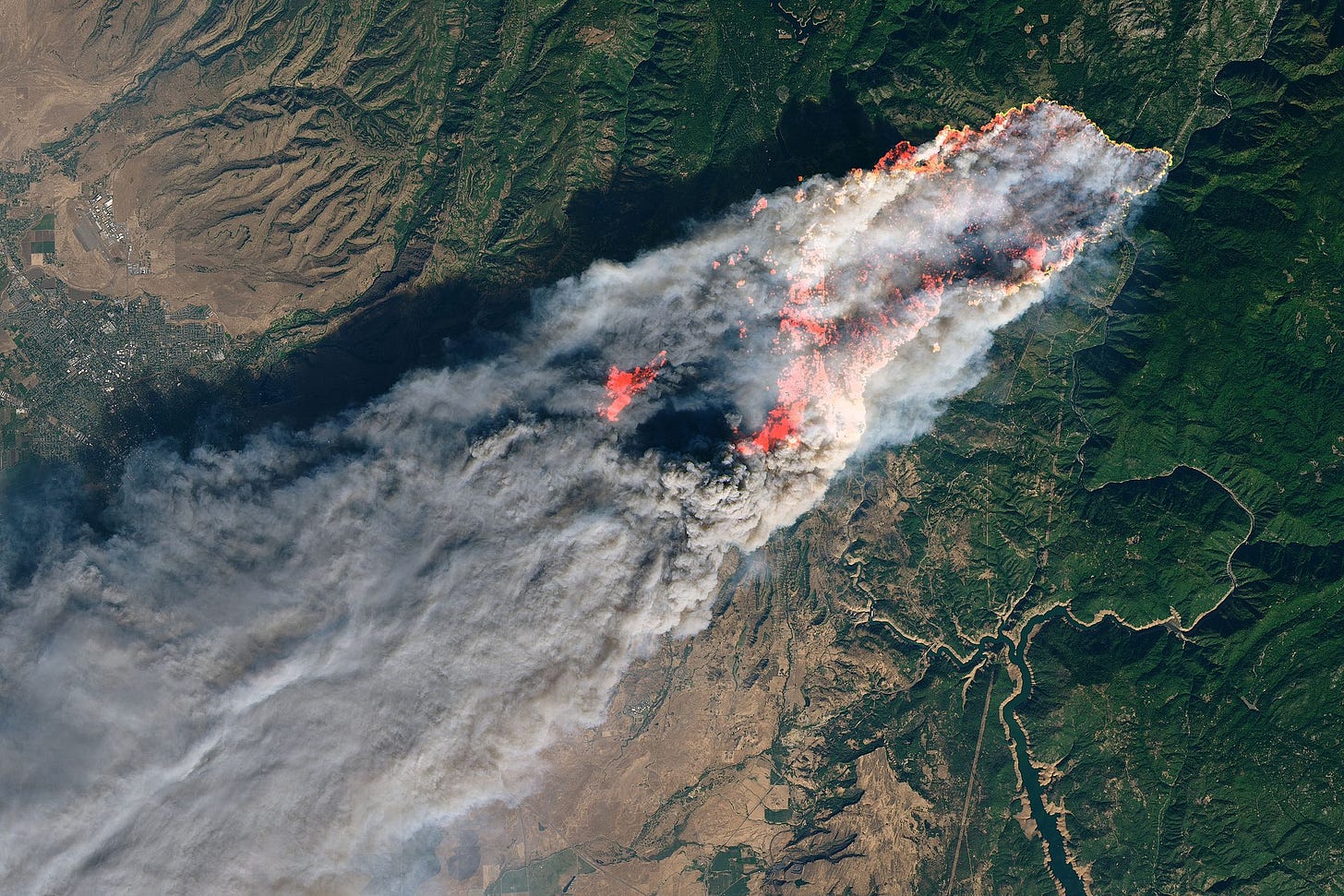

Early on November 8th, 2018, high winds swept into the Feather River Canyon in Butte County, California. PG&E noticed a disruption in power distribution in the area and dispatched someone to check it out. They confirmed that a line had come down and started a fire. By 6:44 a.m., it had already grown to 10 acres.

By the afternoon, the smoke had reached the Bay Area. The light took on an eerie tint. The air smelled like a campfire. News outlets noted how odd this all was.

Unsure of what else to do, I continued biking to work, feeling a sore throat settle in. When I finally began carpooling to spare my lungs, the smoke had become so thick that we could not see the Bay or San Francisco while traveling across the Bay Bridge. Driving felt like hovering across the Bay all the way to work. The ominous gray haze consumed the landscape and my mind.

Eventually, my employer instructed us to work from home until the fires passed. We kept our windows closed but I wasn’t sure if the air inside was any better than the air outside. Even indoors, I felt woozy, like I was at altitude. The rare times I went outside I noticed how oddly cold it was for this time of year. My housemate Matt pointed out that this was because the smoke had blotted out the sun.

In desperation, I decided it was time to order an air purifier. I settled on the Coway 1512 HH Mighty, which was one of Wirecutter’s top-reviewed air purifiers, praised for its effectiveness in small apartments, ease of use, and nifty pollution sensor to gauge indoor air quality. While I was easily persuaded, one Amazon reviewer said this:

“I don’t think the pollution sensor works. I farted next to it and it didn’t even change colors”

Maybe Wirecutter didn’t test this purifier against flatulence. Perhaps some people are just hard to impress.

A few days later, I arrived home from work to meet our newest appliance. It was the size of a bulky old TV and resembled an oversized iPod shuffle. Wanting to waste no time, Matt had already unboxed it and turned it on.

I was grateful to have a device dedicated to cleaning our air, but noticed that no matter how much I ran it, the pollution sensor never changed past red to purple or blue. I was unsure if this was because it wasn’t working or because our air was just that polluted. I also noticed that it made a lot of noise on the higher settings, vibrating like an old washing machine.

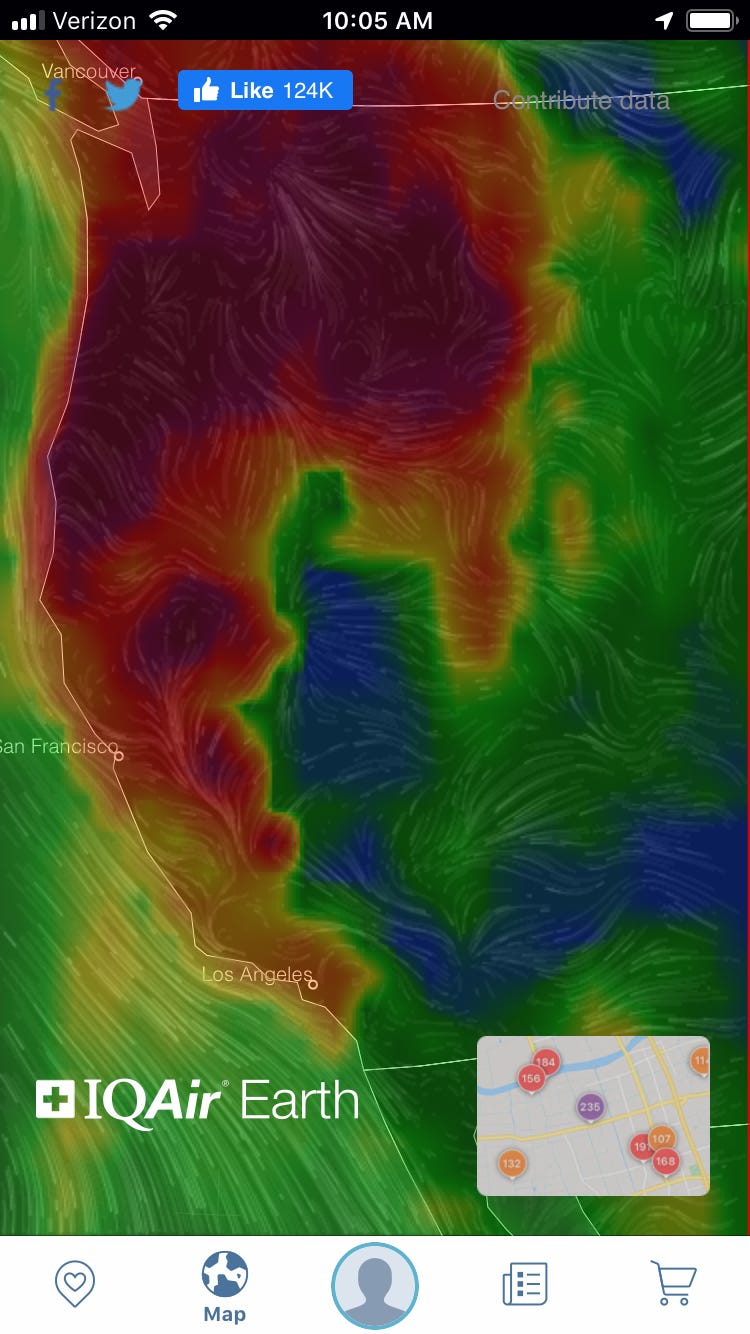

For the next two weeks, air quality was the first thing I checked when I woke up and the last thing I looked at before I went to bed. In moments of self pity, I’d send my East Coast friends screenshots of the air quality map. It looked like the West Coast had a bad rash.

Despite the fires being near Chico, over 180 miles away, they made the air worse and for longer than the nearby Napa fires had. This was due to their size and unfavorable weather patterns.

Air quality depends heavily on the wind, which is a tricky aspect of weather to forecast. Normally, warmer inland air pulls cooler Pacific air into the Bay Area, forming morning fog and afternoon breezes. This acts as natural air conditioning, constantly refreshing our air quality and pushing pollution into the central valley. During the Camp fire in November, an inversion layer had descended on Northern California, trapping the smoke in a dome of high pressure air. The Bay Area Air Quality Management District recorded nearly 2 straight weeks of more than 151 micrograms of particulate matter per cubic meter of air, the longest run in their 63 year history. Anything above 151 is considered unhealthy.

The air improved in late November when a Pacific storm cleared the inversion layer and brought rain to the fire zone. Shortly after, my mom and I met up with a few of her sisters to have Thanksgiving dinner at Balboa Cafe. As we walked from Embarcadero BART to the restaurant, we noticed many others gleefully wandering along the waterfront, grateful to breathe freely again.

The technology behind an air purifier is quite simple. It pulls air through an intake system and passes it through a HEPA (high-efficiency particulate air) filter. A HEPA filter has the same texture as a fine coffee filter, folded into dozens of accordion-like pleats. When used correctly, a HEPA filter captures 99.7% of particles larger than three microns. You can see this work in action. After just one heavy fire season, the filter changes color from as white as Taylor Swift’s teeth to a dismal shade of charcoal.

By the 2019 fire season, after moving in with Alexis, I decided it was finally time to change the HEPA filter on what was now our Coway. I was appalled to find it still wrapped in its factory plastic. It hadn’t filtered any air during the worst fire season on record. No wonder it couldn’t change the pollution sensor’s reading and made such a racket on higher settings. A chill ran through me as I thought about how much smoke I must have inhaled that fall.

An air purifier is useful even outside wildfire zones. Indoor air quality can be quite bad due to gas stoves, mold, pet hair, and other common pollutants. Our first apartment was a tiny in-law unit on Russell Street. Its fire alarm was so sensitive that cooking anything would set it off, earning it the nickname 'the bacon alarm.' In between fire seasons, I used the Coway as a backup hood for smoky brunches.

During the calmer 2019 fire season I’d even use it to clear candle smoke after guests had left a dinner party. This sometimes caused more problems than it solved. Once, I placed a freshly extinguished candle at the base of the purifier to speed things up, only to accidentally kick it while cleaning, splashing hot wax all over the front. Our poor air purifier looked like it had made out with Lumiere from Beauty and the Beast.

Our lil’ Coway got just one year of rest before going back to full-time work in 2020. I had so much more to learn about air quality. The coming fire seasons would be my harshest teachers yet.

Sometime during the claustrophobic fever dream of early COVID, I had an idea for a movie that I thought was original and clever. The premise was a film ostensibly about something else, like a family vacation, where weather and natural disasters gradually shift from background annoyances to onscreen peril. The goal was for climate change to be the real villain and antagonist, with the characters slowly realizing this as they snapped out of their petty, mundane conflicts. It would be a microcosm of our times, like if Get Out, was directed by Al Gore instead of Jordan Peele.

After reading the hauntingly beautiful novel The Light Pirate, I realized that someone had executed my idea better than I ever could. I also understood that the reason I had that movie idea and the reason it will likely never get made are one and the same: we are all already living it.

Anyone living in the Bay Area during 2020 remembers Blade Runner day. On September 9th, 2020, the sun never rose; the skies stayed an eerie pale orange all day. The cause was smoke from the North Complex fire and 20 other fires that had torched 2 million acres of forest east of us. All that smoke hung at an altitude that swiftly extinguished the sun, like a vengeful god.

I remember the primal terror of scanning the sky all day, willing the sun to reappear and save us. It was the first time I viscerally understood why people used to go crazy during events like eclipses and volcanic eruptions. Without modern science, I would have assumed that the gods had abandoned us and would have been willing to sacrifice as many goats as necessary to get them to calm down and bring the warmth and light back.

In an already anxious year with COVID and a tense election, these apocalyptic skies were the last thing I needed. My doomscrolling reached a new level of frenzy. Reading Reddit election coverage and New York Times COVID stories before bed gave me insomnia. Then I’d wake up and get even more anxious while reading wildfire updates, scanning the air quality forecast, weather, and wind map, desperately searching for clues about when things would improve.

I started leaving our apartment less and less. I’d wear my smoke mask to the gym or the grocery store, then swap it out for a COVID-safe mask before going inside. In those terrified, flattened days, the only difference between work and leisure was which screen I was looking at, and the only difference between my leisure activities was which mask I wore.

When I went to change our HEPA filter in 2021, I noted how the ribbed accordion interior of the fabric was now pitch black, covered in foul soot. I shuddered as I removed it, thankful that this time the soot had ended up in our Coway’s lungs instead of mine.

Alexis was an environmental science major at UCLA. She has spent the nine years since graduating in sustainability roles, including corporate sustainability, decarbonization, and green buildings.

She recently started her third year of her part-time MBA program at UC Berkeley.

As the partner of a business school student, I don’t get the education, but do enjoy a contact high from her nightly debriefs and “tea ceremonies” after class. In year one, it was tales of contrarian men who had allergic reactions to the very notion of DEI and doggedly defended CEO compensation packages. Year three’s gossip was less absurd but sadder and more profound.

The final year of her business program has let her take electives that directly relate to her interest in sustainability. During night one of her climate change and business strategy class, Alexis told me about a fascinating pattern. As the professor laid the groundwork for the modern climate crisis via crisp slides displaying grim statistics, man after man (it’s always men) began to raise their hand. They didn’t have questions, but rather sought to poke holes in the professor’s logic.

“These are just estimates, right?”

“This emissions stat says this, but how do we really know that?”

“Aren’t governments famously secretive about this kind of data?”

The professor calmly explained that all emissions data came from reputable sources like direct air measurements and fossil fuel sales data from energy markets. There were no huge inferences or guesstimates on these slides—just basic math taken directly from the oil and gas industry. Governments and companies don’t buy crude oil and natural gas without the intention to combust them. That’s what fossil fuels are for. We burn them to power our world. The emissions are as undeniable an output as the transportation, energy, and heat they provide.

What self-assured men choose to publicly quibble over speaks volumes about their worldview. These men had shown far fewer contrarian impulses during macroeconomics or accounting classes. Yet now they suddenly felt compelled to second guess every slide.

Alexis and I realized this wasn’t because the slides were wrong, but because the alternative felt threatening. We grant disciplines like macroeconomics immunity from inquiry for the same reason we accept the Pythagorean theorem: accepting it doesn’t challenge the stability of the world, hierarchy, or power structures.

Anthropogenic climate change, on the other hand, is an inherently charged discipline. If all of this is really true, then we’re going to have to change our behavior, as individuals, companies, and governments. The last thing an MBA man wants to accept isn’t climate change itself, but a world without true winners, and one where he might personally lose something.

If all of this is really true, we might have to feel sad, small, and scared.

It’s much easier to nitpick statistics than to face their implications.

Men, and especially men in business school are experts at disguising their feelings as logical arguments. Implicit in all their intellectual questions was an emotional plea:

“No—things can’t really be this bad... can they?”

Countries like India, China, Nigeria, and Mexico have grappled with air quality issues for decades. The United States is relatively new to this vexing problem, which is why our discourse and behavior are still catching up to the reality of hazardous air.

Initially, it seemed easy to dismiss wildfires as a regional nuisance—something Californians would have to endure. For a while, I believed this too, seeing the annual fire season as proof that California was doomed while my East Coast and Midwest friends held the climate change high ground. But climate change is a global issue, and smoke doesn’t care about borders. In hindsight, it was naïve to assume wildfires would remain confined to the Western states. Smoke from the 2018 Camp Fire drifted across the country, hazing the skies of New York City—a pattern repeated in 2021. 2023 marked a true reckoning for the East Coast, as my friends and family there dealt with hazy skies and choking air from Canadian wildfires.

People who once claimed they could escape climate change by moving to Canada or Michigan have since discovered that these places face the same air quality issues California does. The idea of a true escape from climate change is nothing but a fantasy for delusional technocrats lacking humility.

Everyone will be impacted somehow, even the rich and the mobile. The beachfront estates in Jupiter, Florida, and the Hamptons are threatened by rising sea levels and furious hurricanes, while Malibu’s hillside enclaves are increasingly at risk of wildfires. These once-desirable areas may soon be considered deathtraps instead of safe havens.

So far, the impacts of climate change have been intensely asymmetrical—inconveniencing the wealthy while devastating the poor. As Bong Joon Ho depicted in Parasite, for the rich and powerful a freak storm means a canceled camping trip, but for others, it means losing homes and lives.

When a home becomes unlivable, the only sane response is to move, yet our political system seems unprepared, or unwilling, to accept this reality. As the climate becomes less hospitable and more unpredictable, new waves of climate refugees will continue arriving at our southern border. One day, we may see today’s migration crisis as mild compared to what followed it.

It all feels like a slow-motion car crash.

What’s central to the climate anxiety of most millennials like me is the cognitive dissonance at its core.

As we discovered during COVID, extreme terror and extreme banality can and do live side by side. Social media only intensifies this peculiar modern sensation. It’s the feeling of knowing all this, yet still loading the dishwasher, chuckling at memes, and listening to podcasts. It’s the urge to scream for help while elected officials in Florida and Texas won’t even mention climate change, fearing losing their next primary. It’s accepting that the coming year is likely to be both the worst it’s ever been and the best it will ever be.

I started writing this piece more than a year ago but hesitated to publish it after last year’s wildfire season wasn’t as catastrophic as expected. Even as Maui and Canada burned, I worried that publishing about wildfires during a seemingly 'quiet' year might feel out of touch, alarmist, or just jinx us. In hindsight, my hesitation feels as absurd as the fact that historically wet places like Maui and Canada were consumed by flames. The right time to speak the truth about climate change is always right now.

As I write this, California has more than a dozen wildfires actively burning. The Line Fire has burned over 37,000 acres in the San Bernardino mountains above Los Angeles and is now large enough to create its own weather patterns. The Park Fire burned 429,000 acres outside of Chico, an area of land more than twice the size of New York City. As necessary but depressing context, that’s right next to Paradise, where more than 150,000 acres burned in 2018. Outside of California, large swaths of western Nevada, northern Utah, central Oregon, southern Idaho, and southwestern Montana have air in the unhealthy to toxic range of 150-200 PPM due to nearby wildfires.

As a child, I took breathing clean air for granted.

As Alexis and I near seven years together and plan our wedding, we've accepted that life on the West Coast means living at the mercy of fires and air quality.

It’s not just the air we can’t count on anymore. Scientists recently reported that no rainwater on earth is safe to drink thanks to “forever chemicals” like PFAS and microplastics. It seems we’ll need to get better at filtering our water in addition to our air.

All of this rattles me on a primal level.

It’s widely agreed that the window for preventative climate measures has long since passed, and that mitigation is now the most realistic course of action. We’ve already opened Pandora’s box with our carbon emissions. Now, we can only batten down the hatches and adapt to the new world ahead.

Given this, it’s unsurprising that my generation talks about climate catastrophe with a cocktail of calm pragmatism and cynical humor. In my friend group, the concept of moving to the upper Midwest—'Duluth is climate-proof'—gets tossed around as casually as phrases like, 'Don’t worry about the fires when the big earthquake comes, the tsunamis will put those right out.”

Yet even when we discuss more upbeat or trivial topics at dinner, our Coway hums quietly in the background, making as much fuss about the changing climate as a Republican congressman.

Though we now own two air purifiers, this year they’ve done little more than filter cooking fumes and candle smoke. The West Berkeley breezes continue to keep our air cool and fresh while heatwaves and fires ravage the rest of the West. Even as I cautiously wait for the wind to shift, I face the fact that where I live is, for now, jarringly pleasant compared to the modern meteorological news cycle. One third of Pakistan flooded in 2022. That same year, Hurricane Ian caused over $112 billion in damages in Florida. Closer to home, Las Vegas recently recorded four straight nights where the temperature never dropped below 90 degrees Fahrenheit.

It’s long been true that much of our world would be uninhabitable without costly, energy-intensive systems—diverting rivers, draining wetlands, irrigating desserts, pumping water over mountains, conditioning sweltering air, desalinating ocean water, and filtering out pollutants. However, climate change means that now more places are becoming inhospitable, hazardous, or even deadly to inhabit.

Buying an air purifier was quietly confessing that I, too, can’t live on this planet without some form of filter or intervention. Like many, I now live in an increasingly precarious state reliant on a technological intermediary.

This is the premise of so many sci-fi stories. Yet while in a sci-fi world an inhospitable planet is a gripping setting for an adventure, in real life it’s a tragedy because we are the ones making a relatively habitable planet less so. Our planet is no longer enough for us because we are too much for it.

Air purifiers are my most concrete connection to this strange new world we all live in. They’re a quotidian reminder of our collective climate peril, an embodiment of the “batten down the hatches” mentality that’s spreading like, non-coincidentally, wildfire. Their sudden ubiquity feels like an admission, if not of guilt, then of powerlessness—an implicit acceptance of how bad things have gotten and will continue to get, proof that the dystopian future I fear is already here.