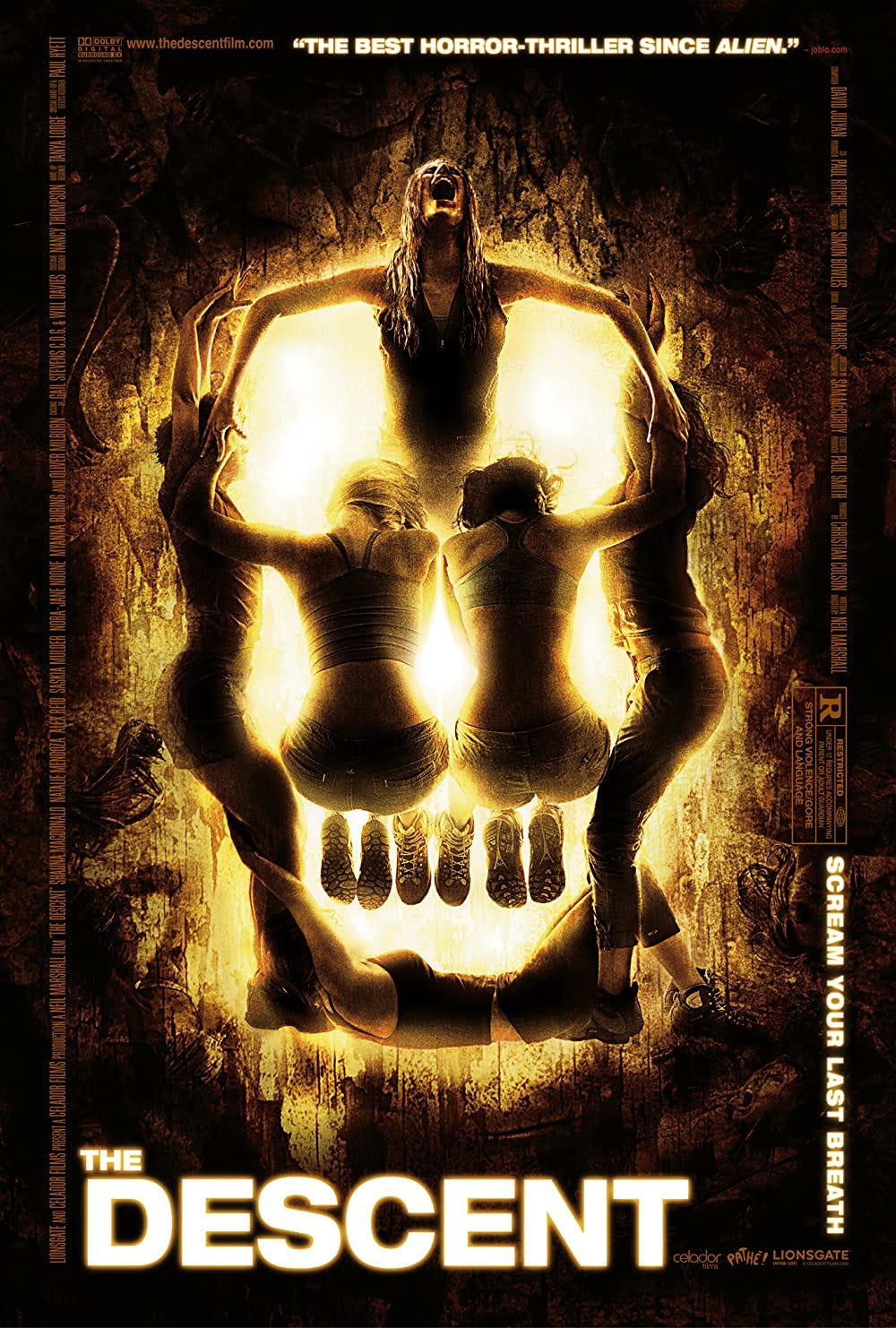

Oughts from the Aughts: The Descent (2005)

My favorite underrated gems from the 2000s, explained in under 2010 words

Authors note: This article contains spooky spoilers for The Descent, which you’ve had 18 years to see, not that I’m counting.

"It cannot be seen, cannot be felt,

Cannot be heard, cannot be smelt.

It lies behind stars and under hills,

And empty holes it fills.

It comes first and follows after,

Ends life, kills laughter."

-J. R. R. Tolkien

“Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And if you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.”

-Friedrich Nietzsche

One of the most exhilarating experiences of my life was exploring the Kazamura Cave system on Hawaii’s Big Island. One fateful May day, Alexis, Lauren, and I spent a few hours in a pitch black lava tube. Kazamura Cave isn’t just any lava tube; it stretches more than 42 miles underground. It’s the deepest known cavern in the US. As intensely as the sensation of being this far underground, I can still recall the unease that went through my brain when our guide insisted on locking the door to the cave behind us so no one else could wander in and disturb it. It felt like the beginning of a horror movie. Later on, after we tried turning off our headlamps to experience the thrill of total darkness I felt a sense of awe followed by this sinister thought: “If anything went wrong right now, no one would hear us scream and no one would ever find our bodies.”

It’s into this exact fear that director Neil Marshall fearlessly rappels in his overlooked 2005 horror movie: The Descent. I made the curious choice to watch this one by myself at night in college and the film’s scares burned their way into my tender brain at age 19. So I knew that Lauren and I had to revisit it together, after we’d made it out of Kazamura Cave alive, of course.

The gist of the plot is that a year after losing her implied-to-be-unfaithful husband and daughter in a gruesome car wreck, Sarah and her four best friends meet up in North Carolina’s Appalachian Mountains for a caving expedition. Leading the bunch is gorgeous and athletic Juno. She’s confident, brash, and shared some steamy eye contact with Sarah’s husband in the prologue. Juno has brought along her chatty Irish adrenaline junkie friend Holly, who rounds out their squad of six spelunking women. While the first act features some cheesy dialogue and a few horror tropes you’ll recognize, it honestly becomes a completely different and much better movie once they descend into the cave.

What impresses me about this film is the discipline it shows in metering out the suspense and setbacks. One of the scariest scenes early on involves nothing more than some narrow passageways and letting us imagine the claustrophobia and stress of trying to wriggle through them. Things start to go South when there’s a cave in, trapping them underground. Then there’s deception to grapple with: Juno has lied them and led them into an uncharted cave system instead of the one they all agreed on, which Juno dismissed out of hand as a tourist trap. Juno’s hope of reconnecting with her friend Sarah on this uncharted adventure has already gone off the rails and now they have to band together to find a way out.

The Descent does some of its best work as a fairly believable study in Murphy’s Law. The things that you expect to go wrong do, then unexpected things start to go wrong, and the panic, claustrophobia, and paranoia of the situation burrow into your spine and won’t leave until the film is over. The setting and situation are well chosen and you can feel your own survival instincts kick in watching these women try to survive. Being trapped in a cave conjures up a powerful, primal fear in all of us can relate to so you feel the panic and disorientation of their situation as powerfully as they do. Indeed the biggest threat for much of the film is our oldest childhood fear: darkness. As the beams of the women’s headlamps and glow sticks futilely stab light into the menacing darkness all around them, an overwhelming dread creeps in as you realize just how alone they are. Then, a different species of terror crawls into frame as you begin to suspect they may not be alone in the dark after all.

Yes, like the filmmakers, I’ve been hiding the fact that there are monsters in this movie up until this moment. What a reveal this ends up being. The monsters first appearance is the best jump scare in the film and one of the best ones of all time in my opinion. I normally hate jump scares. They’re widely regarded to be one of the laziest parts of modern horror, however this one was pitch perfect in execution and timing. The cinematography choice to use the frantic panning of a digital camera to reveal the location of the first monster incorporates some of the raw terror of the found footage genre. Moreover, a jump scare actually makes sense within the world of the cave. Since the monsters are ambush predators that hunt in the dark, showing up in unexpected places isn’t just extra frightening; it’s a realistic depiction of how they would go after prey in the dark caves that they know like the back of their pale and slimy hands.

It’s me, hi, I’m the monster it’s me.

When they do get their 15 lumens of fame, the creature design is scary, though perhaps not original. The monsters or “crawlers” are blind humanoids evolved to hunt in total darkness. They look like more athletic versions of Gollum and are quite unsettling to watch. They scream in the blackness like bats trying to echolocate and these piercing cries rattle your nerves as much as their wan appearance and sharp teeth do.

The screenplay is also wisely judicious with the monsters. They appear later than you’d expect, though a keen eye will spot some clever foreshadowing. Most importantly, we are already quite scared and rattled by how much has gone wrong before a single monster shows up on screen. Like the women, we’ve had to endure claustrophobic passageways, a harrowing cave in, bickering and infighting within the group, with the terror of the darkness and weight of the cave constantly pressing in all around us.

Your mind, like Sarah’s, runs wild speculating what might be out there before you ever see what actually is. At one point Sarah’s friend even tells her after the cave-in: “Look the worst thing that could have happened has already happened and you’re fine.” Oh how bloody wrong she turned out to be. The monsters that appear embody our deepest fears about what might be lurking in the dark.

In the stagnant cave air of Hollywood horror tropes, what’s refreshing about The Descent is that it’s got an all female cast but doesn’t play this choice for sex appeal. While not all of the characters are as fleshed out as the protagonists, they’re still believable, smart, and competent women who have different moments to showcase their strengths, weaknesses, and personalities in the cave. During production, the studio wanted a scene featuring the ladies stripping down to go for a swim, but director Neil Marshall fought them on this, arguing it would make no sense and cheapen the movie. Thank God for that decision.

For such a visually & thematically dark movie, it also incorporates color in creative ways. Certain shots are so evocative and saturated with pain and intensity that they look like they could be a Goya painting. With natural light off the table, the cinematographers get creative with light sources like glow sticks, flares, headlamps, and even the greenish gray pall of a digital camera display. The blood red light of glow sticks dominates certain sequences and makes them feel like a Dante-esque descent into hell.

Be warned that this is an unapologetically grim film. There are scenes of violence and terror that make the bone-crunching climax of 127 Hours look merciful in comparison. Left to fend for themselves in a dark cave system with no clear way out, the women slowly descend into madness and violence as they are pushed to their breaking point. With monsters scratching and clawing to rip their throats and intestines out, their only choice is to scratch and claw right back.

The Descent ultimately succeeds by deftly weaving together multiple types of movie at once. There’s a taught wilderness survival thriller, a spooky monster encounter, the unraveling of a friendship, one woman’s descent into madness, and a provocative parable about making peace with death.

Like later prestige horror like Midsommar and The Babadook, The Descent is a story about trauma, what it does to individuals and friendships, and what it takes to overcome it. Sarah has a particularly iconic moment of baptism by blood where after emerging from a murky pool looking like a swamp monster, she defeats multiple crawlers, confronts the friend that’s betrayed her, and makes for the surface by herself. She has lost all of her friends but also found the will to live. As she bursts out of a crevice in the ground, bloodied and wild-eyed, it’s hard not to see the visuals as a literal and metaphorical rebirth.

In the American version of this film, Sarah escapes the cave, briefly seeing her friend’s bloodied ghost in the passenger seat of her car before the credits roll over the group photo they took before going caving.

In the much bleaker British ending, we then cut back to Sarah imagining her dead daughter’s birthday cake only to realize that the light of the candles is actually the light of her torch. She’s still trapped deep in the cave, having hallucinated the escape we just saw. She looks grimly at peace with her fate to never leave the cave and ready to meet death head on. As the camera begins to zoom out we take in the blackness around her and hear the unsettling sound of dozens of crawlers racing towards her.

While the American ending is more hopeful, in both endings the darkness of the cave eclipses the fragile light of humanity. I’ve even heard a provocative but flimsy fan theory that there are no monsters- they’re all figments of Sarah’s traumatized imagination and she commits all the violence herself. The real monster was the one with the pick axe. Woah.

The Descent doesn’t hit the same type of highs as prestige horror gems like Get Out or Midsommar, but it’s still one of my favorite horror films from the aughts. This is partly because it epitomizes a type of movie that has basically gone extinct: the mid-budget film. As movie audiences have dwindled over the past 15 or so years, Hollywood started focusing on surefire blockbuster gold, hence the dominance of superhero movies and the endless parade of prequels, sequels, reboots, and remakes. Known IP is the only safe bet anymore, which is why outside of A24’s horror films, everything else that’s scary is a derivative remix of The Conjuring’s jump scares. Yet there was a magical time where people took a chance on a relatively unknown British director and let him make a dark “chicks with picks” horror thriller. It’s into this mysterious crevice of horror film history that I happily crawled to experience my anxious imagination’s greatest hits of things that could go wrong while caving. What a thrilling and harrowing descent it was.

Wait, what’s that crawling in the background?

If you enjoyed reading this and want to support more content like this please, consider becoming a subscriber if you aren’t one already. A free or paid subscription is a great way to support my writing.

Do you know someone that would enjoy this article? Share it with them!

If you’ve got thoughts or questions about this post, I’d love to hear them.