Sociology to Save Your Life: Rationalization

How the hunger for efficiency created a world starved of humanity

Shopping at Target is terrible now.

Safeway, also terrible.

CVS has always been terrible, which is why I stopped shopping there years ago.

If I went back, I’m sure it would greet me with the same uniquely depressing energy.

Why is this?

Target used to be characterized by well-designed stores full of a delightful mix of necessities like laundry detergent and dental floss, and fun home indulgences like scented candles and throw pillows.

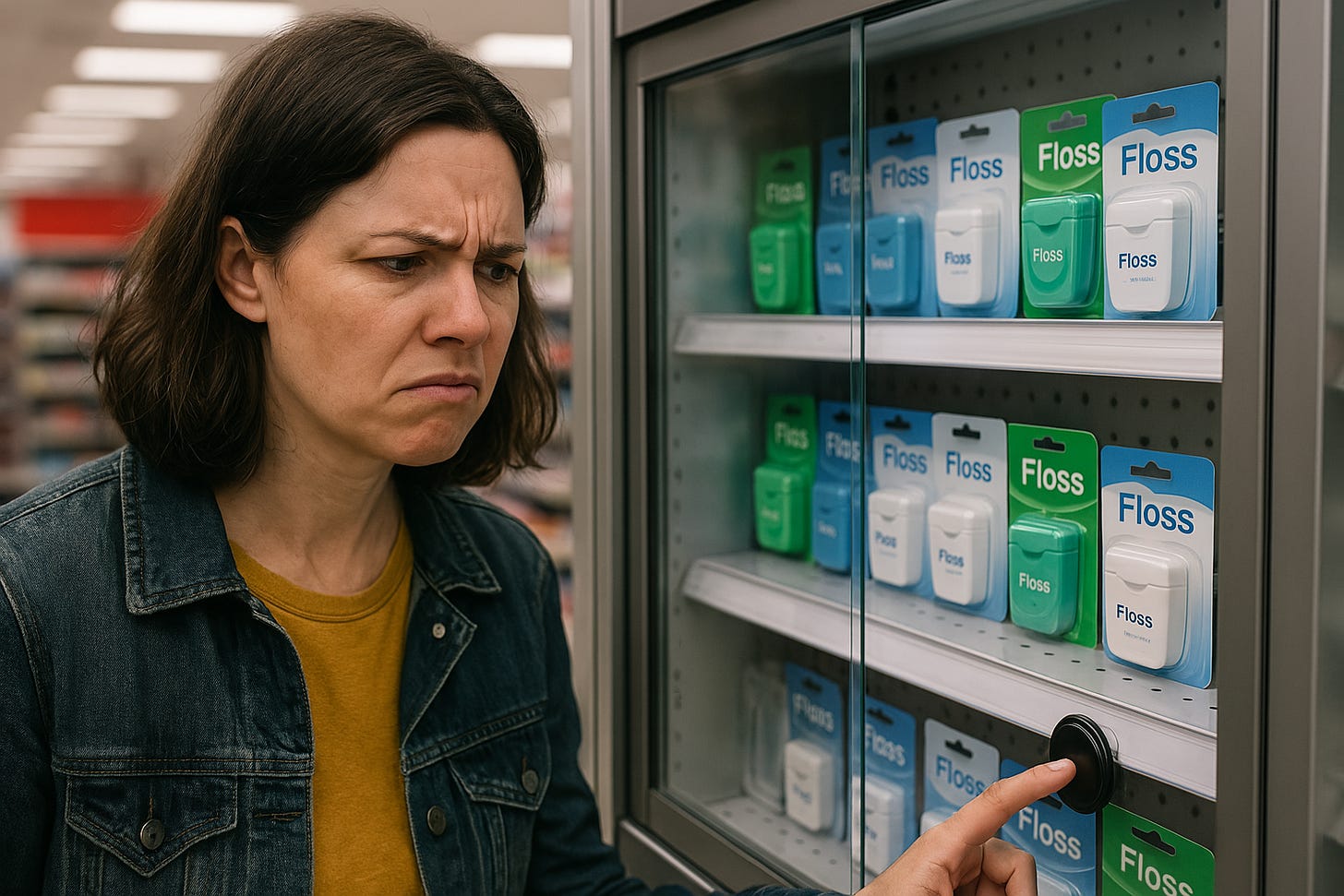

Now, by my count, three-quarters of the inventory is imprisoned behind plexiglass.

To buy any of it—especially the home essentials you came for—you have to press a button and wait an indeterminate number of minutes for a beleaguered employee to unlock the floss fortress. Safeway is the same way.

In theory, this should only add a moderate amount of friction to the shopping experience, but in practice it takes 5-25 minutes for anyone to show up, by which point there’s a line of comparably frustrated customers all equally pissed that they need to be given permission to buy floss. Compounding matters is that all stores are now routinely understaffed, adding to wait times and the perpetually dour vibe of retail these days.

Both the plexiglass and the understaffing trace back to the same root cause. Caging dental floss in plexiglass was almost certainly an edict from Target’s C-suite after someone in Minneapolis looked at a spreadsheet detailing how much of a loss they were taking from shoplifters. After digging into the data, they arrived at the conclusion that the only way to preserve their profit margins was to install plastic barricades around the most commonly shoplifted items like floss. Similarly, replacing staff with self-checkout (where you are essentially an unpaid employee of Target), was another cost-cutting measure. People are expensive. Maximizing profit means employing as few as you can get away with.

These measures aren’t dumb. They’re logical.

That’s the problem. While the spreadsheets make sense, the outcomes don’t. Often, the extreme desire for efficiency results in experiences that are cold, alienating, and off-putting.

Ever since Target began incarcerating their inventory, the experience of shopping became so slow, clunky, and unenjoyable that Alexis and I stopped going. Sometimes I remember to restock the essentials I used to go to Target and Safeway for at Berkeley Bowl, Mi Tierra, or our neighborhood grocery store: Franklin Brothers.

The sadder truth is that more often we just buy it from Amazon.

Despite knowing full well how horrific Amazon’s record on worker treatment is, the siren song of infinite inventory, fast delivery, and free shipping is too hard to resist—especially when I’m busy, tired, or overwhelmed, which is often. I know that my growing dependence on e-commerce is part of why brick-and-mortar retail has been dying for decades. But I also feel largely powerless to change any of this. So I do what most people do: I prioritize my own comfort.

My cognitive dissonance is loud—but not louder than my desire for convenience.

And this, I’d argue, is the essence of the much bigger, more unsettling story: how the modern world keeps getting more efficient and comfortable while also becoming increasingly unbearable to live in. What’s more disturbing is that sociologist Max Weber saw this coming more than 100 years ago.

I say: Target sucks now.

Weber would say: Target sucks because our entire society is governed by the cold logic of rationalization.

This distinction is why Weber’s writing is still being read a century after his death and why mine will likely disappear into the algorithmic ether, never to haunt a college syllabus, eclipsed by a push notification about a celebrity breakup or a meme about oat milk.

Weber defined rationalization as the process by which intuitive, emotional, or moral thinking is replaced by reason, logic, and efficiency.

To be clear, doing things rationally or efficiently isn’t inherently bad. Weber observed that problems arise when we start doing things in the most calculated, predictable, and efficient way—even if it strips away humanity, morality, or meaning. This leads directly to Weber’s central concern: how rationalization, once institutionalized, plays out in bureaucracies. He called this “the iron cage” of modern life: systems that run efficiently, but often feel soul-crushing.

The beauty and utility of this sociological concept, like all the good ones, is that you don’t need to have studied sociology or even care about intellectual frameworks to apply it to your life and get value out of it. If you’ve ever shouted “representative” into a phone tree, you’ve met the iron cage.

Para continuar en español, oprima dos.

Our world is saturated with hyper-rational systems—maddening mazes of bureaucracy that strangle our joy and quietly drive us insane: self-checkout machines that freeze if you don’t bag your item just so; multiple paper notices from your bank cheerfully confirming your enrollment in paperless billing; and the barely concealed hostility from your insurance company when you dare to suggest that you'd actually like to use the services you've been dutifully paying for, instead of just funding them until you die.

After college, my sister lived in Buenos Aires for a few years. She told me that Argentina is so full of bureaucratic nonsense like this that Argentine Spanish developed a new word for it: Un trámite. A trámite is never just a task, but rather a quest through Kafkaesque systems where you're sent from one office to another, asked to bring forms you were never told you needed, spending hours on something that could have taken minutes, and generally made to feel like you're the irrational one for expecting logic.

This isn’t just a Latin American quirk. The\is same experience shows up everywhere—just in different packaging.

It would be easier—but less honest—to say this is all the fault of evil people trying to make our lives harder and themselves richer. That explanation is satisfying. But it’s also incomplete.

These systems exist—and endure—not because they’re malicious, but because they’re efficient. They serve their purpose. They deliver results. And in a world wired to reward outcomes, that’s usually enough.

But here's the harder truth: we’ve learned to play along. We accept the logic because, on some level, it works for us too. We like fast shipping. We like low prices. We like optimized schedules. We like the illusion that with the right tools, we might finally get it all done. And so we contort ourselves to fit the systems—shaving off spontaneity, flexibility, and, too often, basic human decency.

What this forces us to admit is that efficiency isn’t an unequivocal good, and that it has always come at a cost. Too often, what gets sacrificed isn’t just waste or redundancy—it’s the human stuff: patience, dignity, eye contact, kindness, time to think, space to feel. The real tragedy of rationalization isn’t just that it makes life harder. It’s that it makes us forget what life is supposed to feel like—and how easily we can become participants in our own dehumanization.

It’s tempting to think the iron cage is something we get trapped in. But often, we build it ourselves. We’ve absorbed the logic of optimization so deeply that we now apply it to how we rest, how we relate, and how we spend a weekend.

Take the idea of free time.

Thanks to the labor movement’s push for the five-day workweek and the advent of time-saving devices like dishwashers and washing machines, we’ve been steadily gaining more discretionary hours since the Industrial Revolution.

So what are we doing with all this time?

The research suggests we’re mostly looking at our phones and streaming content. But more revealing is how we feel about our time: Does anyone you know honestly feel like they have enough of it to get everything done?

Why not?

In his quietly radical book Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, Oliver Burkeman picks up where Max Weber left off—showing how the logic of efficiency hasn’t just colonized our institutions, but also our sense of self.

He offers a stark diagnosis: any success in managing time tends to be immediately offset by a rise in expectations. The paradox of modern life is that the more efficient we become, the more we’re expected to do, and the more we expect ourselves to be able to do. As tools like smartphones and laptops have made it possible to be productive anytime, anywhere, we’ve absorbed the message that we should be productive anytime, anywhere.

For companies, this kind of efficiency is about profit. For individuals, it’s usually about staying afloat—at least at first. But even when it starts as economic necessity, the logic still permeates our lives: time must be maximized, rest is suspect, and we should be able to do it all.

We don’t just apply rationalization to our jobs and errands, we increasingly bring it to our leisure time, too. When we try to rest, we’re now haunted by the awareness of everything else we could be doing: text that friend back, order that shirt, book that vacation, finally schedule that appointment. Compounding this is the fact that our capacity to generate new tasks—new possibilities, new “shoulds”—is now essentially infinite. Our phones offer a never-ending feed of things to buy, try, improve, or respond to. There is always something or someone else waiting in the wings. Rest used to be a reprieve. Now it’s another arena for self-optimization—or a fresh source of guilt and burnout.

Thus arises the Sisyphean rhythm of modern life. The faster we learn to clear the decks, the faster they fill right back up with more stuff.

If you feel like you’re in a never-ending arms race with your to-do list, I have good and bad news. The good news is: you’re not alone. The bad news is: everyone else is fighting the same battle.

I won’t spoil Four Thousand Weeks—everyone should read it. But I will say this: the solution Burkeman offers is both counterintuitive and liberating. The appeal of the endless scroll, the optimized self, the overflowing to-do list, Burkeman argues, is not just about getting things done. At the heart of our obsession with efficiency is a quiet denial of death—a refusal to accept our limits. We chase productivity not just to complete tasks, but to convince ourselves we might escape the final constraint: time.

The struggle is compelling. But it’s also doomed.

You won’t beat rationalization by out-rationalizing it. You don’t win by becoming more efficient. You find freedom—or at least find peace—by rejecting the premise that the point of life is to do more than everyone else. The real task is to identify the few things that truly matter to you, and to give them your time, fully, unapologetically, and at the expense of everything else. That means making peace with all that you didn’t do, can’t do, and never will do.

The paradox is that this feels like giving up—but it’s actually a kind of triumph. None of us will ever do it all. But if we’re lucky, we’ll do some of it. And if we’re wise, we’ll let that be enough.

The larger value—and terror—of Weber’s concept in 2025 is that it’s everywhere.

Rationalization isn’t just an idea from a dusty sociology textbook; it’s the air we breathe. It’s baked into the systems that structure our lives. And, in its most extreme forms, it dehumanizes to the point of devastation.

Take the killing of UnitedHealth Group executive Andrew Witty by Luigi Mangione—a horrifying act that sent shockwaves through the media and corporate world. In its most disturbing form, Mangione’s decision to murder Witty was, in his mind, a protest against the state of American healthcare. The modern American healthcare industry is what it looks like when rationalization metastasizes into something inhumane—a system ostensibly built to deliver care, but in practice designed to deliver profit by providing as little care as legally possible.

What struck me about this crime wasn’t just the act itself—it was the reaction. Corporate violence is treated as normal. Personal violence is treated as unthinkable. This is not a justification of Mangione’s actions. But it is a confrontation with the asymmetry of violence in modern life.

When someone responds to that asymmetry with violence of their own, it forces a reckoning we’d rather avoid: What kinds of violence do we quietly accept every day, simply because they wear the mask of process or profit?

Understanding why something happens isn’t the same as condoning it. But ignoring the conditions that produce it doesn’t help us prevent the next one either.

Weber’s “iron cage” feels so relevant today because it suggests is that we are not actually trapped by overt tyranny—we are trapped by systems so rational, so automated, so normalized, that their cruelty no longer looks like cruelty. It just looks like how things are.

This isn't isolated to healthcare. This is what happens when the pursuit of efficiency becomes unmoored from ethics and we see it, to varying degrees, in insurance companies that profit by denying coverage, in education systems that reduce learning to test scores, in social media platforms that optimize for engagement over well-being, and in gig economy apps that turn human labor into data points to be optimized and discarded.

We’re seeing it play out in real time with Elon Musk’s DOGE—the Department of Governmental Efficiency—gutting public institutions and laying off workers in the name of streamlining. Programs aren’t being cut because they’re failing, but because they aren’t deemed “efficient” enough. And suddenly, we’re all being forced to confront a remarkably simple but tough question: what is government actually for—and who is it supposed to serve?

History offers even darker versions of this. If you want to see this dynamic in its most chilling form, look no further than The Zone of Interest, Jonathan Glazer’s recent film about a Nazi commandant’s idyllic domestic life next to Auschwitz. One of the most harrowing scenes comes when Rudolf Höss and his officers review the specs of newly designed crematoriums. They talk about units processed per day, efficiency gains, architectural plans—marveling at their improved throughput, all without acknowledging, even in euphemism, that what’s being “processed” are the bodies of murdered Jews. The horror of the scene isn’t just what’s happening—it’s that no one in the room finds it unusual. There’s no shouting and no blood, just professionals, calmly evaluating performance metrics.

That is the true terror of rationalization: when a system becomes so focused on efficiency, on smooth operations, on optimization, that it can facilitate—or even conceal—atrocity. Glazer’s film, like Weber’s writing is valuable because it teaches us that for evil to prevail, morality doesn’t need to be shouted down. It just needs to be quietly managed out of the process—replaced by the cold, clean, and indisputable language of optimization.

I know—it might sound alarmist, even intellectually sloppy, to jump from my frustration with buying floss at Target to drive by discussions of time management, Luigi Mangione, DOGE, and a cinematic depiction of the Third Reich. I’ve roasted Malcolm Gladwell for exactly this kind of tonal whiplash in my scathing review of his worst book, Talking to Strangers. But my intent here isn’t to imply that these examples are equivalent; it’s to show how some of the most benign and horrific parts of modern life operate around the same logic. More importantly, they remind us that rational systems are never neutral. They reflect whatever we choose to optimize for.

We could create a system that maximizes the efficiency of library books getting into children’s hands, or one that ensures people spend less time on hold and more time actually getting their questions answered. We could build systems that make it easier to access mental health care, eat healthy food, or find a home to live in.

Efficiency, in itself, isn’t the villain. We just tend to build systems that are ruthlessly efficient at protecting capital, not people; at maximizing output, not dignity. The tragedy isn’t that we use optimization—it’s what we choose to optimize for.

This question is topical because none of this is theoretical anymore.

With self-driving cars already zooming across San Francisco and AI poised to reinvent humanity as we know it—collapsing tasks that once occupied multiple paid humans into milliseconds of machine labor—now is the perfect moment to ask: Who is efficiency really for? What will we do with the time we save by outsourcing undesirable work to large language models? And what happens to the people whose jobs AI eliminates in the name of productivity?

Weber could only give us the language for the iron cage. What we do with that understanding is up to us. Personally, just having the proper words to describe them makes these moments feel slightly less maddening. When I end up in a Target or somewhere comparably hellish, I remind myself: I’m not crazy. The system is.

It’s easy to feel powerless inside systems this vast, this optimized, this indifferent.

But one of the most radical—and reassuring—truths of sociology is that society isn’t something that just happens to us. It’s something we make. Every system we live within was imagined, built, and reinforced by people. Which means it can be changed by people, too.

This helps give us vital perspective. When a system is this big and entrenched, maybe the point isn’t always to win—it’s to notice what it’s doing to us, and to not let it remake us in its image.

And the truth is, every kind of refusal matters: pausing instead of optimizing, laughing at the absurdity instead of internalizing it, choosing kindness in spaces designed for speed. Remember that slowness, friction, and even a little waste aren’t always problems to solve, sometimes they’re signs that something human is still there.

For Christmas, I got Alexis a T-shirt of Moo Deng, the celebrity pygmy hippo, that said: “Become Ungovernable.”

In that spirit, today I say: become unmeasurable.

In the end, life isn’t something to manage—it’s something to stumble through, feel deeply, get curious about, laugh at, and occasionally be surprised by.

And no, I still haven’t gotten that floss. The exhausted employee only had the key for the dish soap, and there were a lot of other people waiting.

But at least now we both know why it was locked up.

Ezra Klein has been pointing this out about "DOGE" which is that "Efficiency" cannot exist in a vacuum. Obviously it's bad faith from the start and the actual goal is to destroy things they don't like or feel culturally opposed to, but even taken at their word, "Efficiency" has no meaning until you attach it to a goal or an outcome. More efficient health care... ok- more efficient at providing the care to everyone? to certain people? at taking payments? at shortening wait times? at clarifying decisions up front?