“I have two lovers in life that I’ve never slept with: the city of Paris and potatoes.” -Francis Mallmann

“Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try Again. Fail again. Fail better.” -Samuel Beckett

I knew just enough about my ancestry to be certain they’d be upset to see me wasting potatoes.

Another batch of Russets had sprouted before I could use them. I took one look at the alien tendrils emerging from their sides and knew I’d procrastinated cooking them for too long. The compost bin seemed like the only option, but I had one last trick to try.

While working at Imperfect Foods, I’d learned that you can regrow many store-bought vegetables from scraps. Kevin Espiritu from Epic Gardening shared this during a podcast interview, painting a picture of an endless conveyor belt of scallions, celery, and bok choy coming back with a new lease on life.

Potatoes are particularly suited for regrowing. What we view as French fries is what the potato views as a starchy battery to power the next generation. Its stored energy pushes those purple and green tendrils upwards, seeking sunlight and moisture. Every sprout on a neglected potato can regrow an entire potato plant.

It’s magical—or agricultural, depending on who you ask.

All you need to do is trim around these “eyes” and plant them facing the sky. Since each potato contains up to ten eyes, one pound of sprouting potatoes can yield up to ten pounds to eat. While cabbage technically yields the most pounds of food per acre, no one gets excited about fried cabbage. Samwise Gamgee would never extol the many uses of cabbage. Potatoes are where it’s at.

I cut the sprouted potatoes into chunks. Then I planted them in some pots and promptly forgot about them. Months later, green leaves burst from the soil like the limbs of a vengeful kraken. I realized I’d never seen potato leaves before.

These ones seemed short-lived. Soon they turned yellow and withered. No amount of water seemed capable of reviving them. I assumed I’d killed my potato experiment.

While cleaning out one of these pots months later, I yanked out the desiccated leaves and was astounded to find several apple and golf ball-sized potatoes in the soil. I did a double take.

It felt like a prank, as if someone had hidden potatoes in my garden overnight. Harvesting potatoes has this surprised quality to it, like a horticultural Easter egg hunt. I was delighted to find each pot laden with even more potatoes. What a glorious, unexpected harvest. What a wonderful plant.

Although I’d eaten and cooked with potatoes all my life, I’d never considered growing them until this moment. Now I needed more.

I went to the nursery to buy more potatoes to plant but the store employee informed me that it was the wrong time of year. Undeterred, I went straight to the supermarket and bought more Russets, determined to replicate my experiment

Gardening experts warn against growing store-bought potatoes for four good reasons:

They have been sprayed with anti-sprouting agents.

They are bred for flavor and yield, not for seed viability.

Seed potatoes are bred to sprout well and are tested for deadly pathogens like potato blight.

Putting a sprouting supermarket tuber into your garden can end up killing off your potato crop and ruining your soil forever.

Learning this last fact shook me. As an anxious gardener and descendant of Irish immigrants, the prospect of backyard potato blight was sobering. To be safe, I kept my experiment in pots.

The next crop humbled me. The yield was much smaller than I’d hoped. This either proved that supermarket potatoes weren’t meant for the garden, or that it was foolish to try to growing them out of season, even in Berkeley.

Come early springtime, I decided to order seed potatoes online. When my Adirondack Blues arrived I was delighted to discover that they were a majestic shade of deep purple. I treated them reverently, determined to make the most of my crop. First, I placed them in a sunny area to sprout, a process called chitting. Then, once the eyes had appeared, I carefully carved each potato into 2-6 chunks, each centered around a sprouting eye. I placed these sprouting chunks on a drying rack to “cure.” Putting them into the ground immediately could cause the freshly cut flesh to rot. Once they had dried, I planted them, eyes up. I watered them, gave them my blessing, and waited.

Potatoes are the fourth most popular crop in the world behind rice, wheat, and corn. It’s not hard to see why. They’re astoundingly easy to grow. They have high yields. They’re an incredibly efficient use of land. While it takes nearly 3 square meters of land to produce a kilogram of rice, wheat, or corn, potatoes require less than 1 square meter to yield that much food.

A single potato is packed with carbohydrates and a surprising amount of vitamin C, potassium, and vitamin B6. They seem designed for storage. The Inca would freeze dry them in the Andean highlands.

We owe a huge debt of gratitude to the Andean people who first domesticated them. All four thousand varieties of potato, from the humble Yukon Gold to the boutique La Bonottoe (grown only on the French island of Noirmoutier) emerged from this spectacular feat of alpine agriculture. While potatoes originated in South America, today they’re grown all over the world. The potato found one of its most enduring and infamous homes when it arrived in Ireland in the late 1500s.

Potatoes thrive even in poor soil. This was crucial for what was ahead, as the British had forced the native Irish off of the best land. So the potato, like the Irish, had to make the best of a bad situation.

Irish farmers would grow potatoes in “lazy beds,” a method particularly suited to the boggy land of the Irish countryside. This method minimizes tilling and is labor-efficient, making it ideal for small-scale farming on rough or uneven terrain.

First, farmers would divide a plot of land into three-foot-wide strips. Then they’d dig trenches on either side, mounding the soil into the middle to create crude raised beds. These beds would be fertilized with organic matter like manure or compost. On the windswept Aran Islands where they shot The Banshees of Inisherin, they’d use seaweed for fertilizer. Cheers to Irish ingenuity.

They’d place seed potatoes in the lazy beds with their sprouts facing towards the overcast skies. Once the plants flowered and the foliage died back, they’d know it was time. Harvesting was as simple as rolling the potatoes out of their shallow beds.

Most of us associate potatoes and Ireland with another word. Potato blight, or Phytophthora infestans, originated in Toluca, Mexico but crossed the Atlantic thanks to the newly thriving concept of global trade routes. The damp Irish climate was as hospitable to the blight as it had been to the potatoes.

The rural poor in Ireland, who subsisted almost entirely on potatoes were devastated when the blight caused the potato crop to rot, starting a famine in September 1845. Lasting seven years and claiming one million lives, this crisis was more than a natural disaster— like everything in Ireland, it was political. Under British rule, response to the Irish plight ranged from indifference to annoyance. Despite the famine, Ireland was forced to continue exporting food to Britain. British landlords demanded rent from their destitute tenants, leading to mass evictions. While the British didn’t cause the famine, they made it much, much worse.

The catastrophic failure of the Irish potato crop is a major reason why Ireland’s population today is smaller than in the 1800s. It also explains why so many people of Irish descent now live in the United States, Canada, and Australia.

Athlone sits in the heartland of Ireland, situated halfway between Dublin and Galway. Straddling the Shannon river, it’s split up the middle between County Roscommon and County Westmeath. It boasts a historic castle that once controlled the strategic river crossing, and Sean’s, allegedly the oldest pub in Ireland.

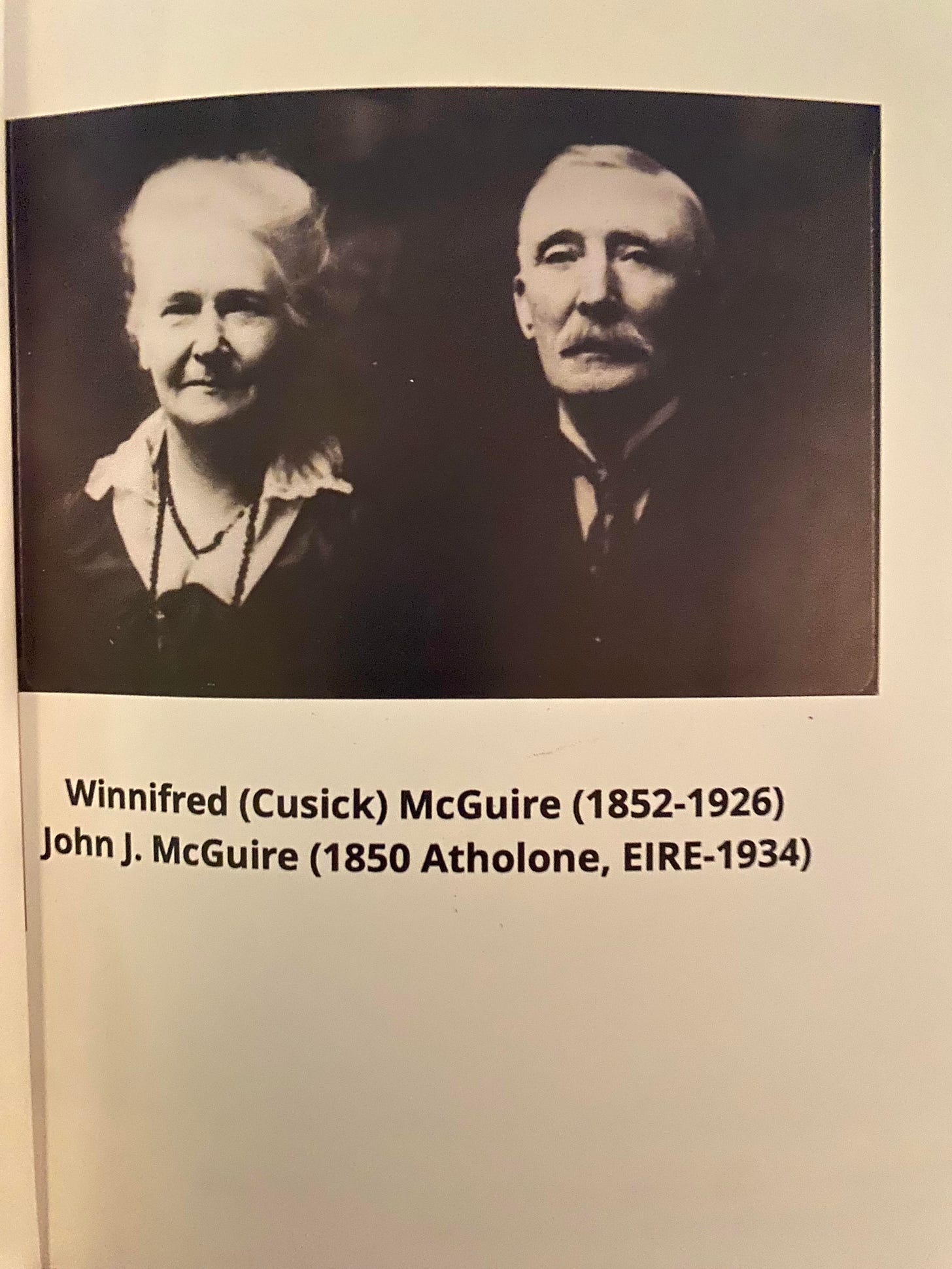

No one knows exactly why John J. McGuire left Athlone. What is certain is that he was born there in 1850, five years into the famine.

Last summer, after years of curiosity about my Irish ancestry, I sought definitive answers. I visited the Museum of Irish Emigration along the Liffey River where I’d arranged to meet with a genealogist. He quickly found microfilm of my great-great-great-grandfather’s baptism records and suddenly, years of vague Irishness slid into unambiguous focus.

The genealogist spoke with a brogue so charming I would have happily listened to him read the terms and conditions of esoteric software. He instead held court on the comings and goings of my ancestors.

John J. McGuire emigrated to the United States, arriving in Boston. He married Winnifred Mary Cusick in 1869, at age 19. They moved to Milwaukee, where he worked as a plumber, and later settled in Minneapolis.

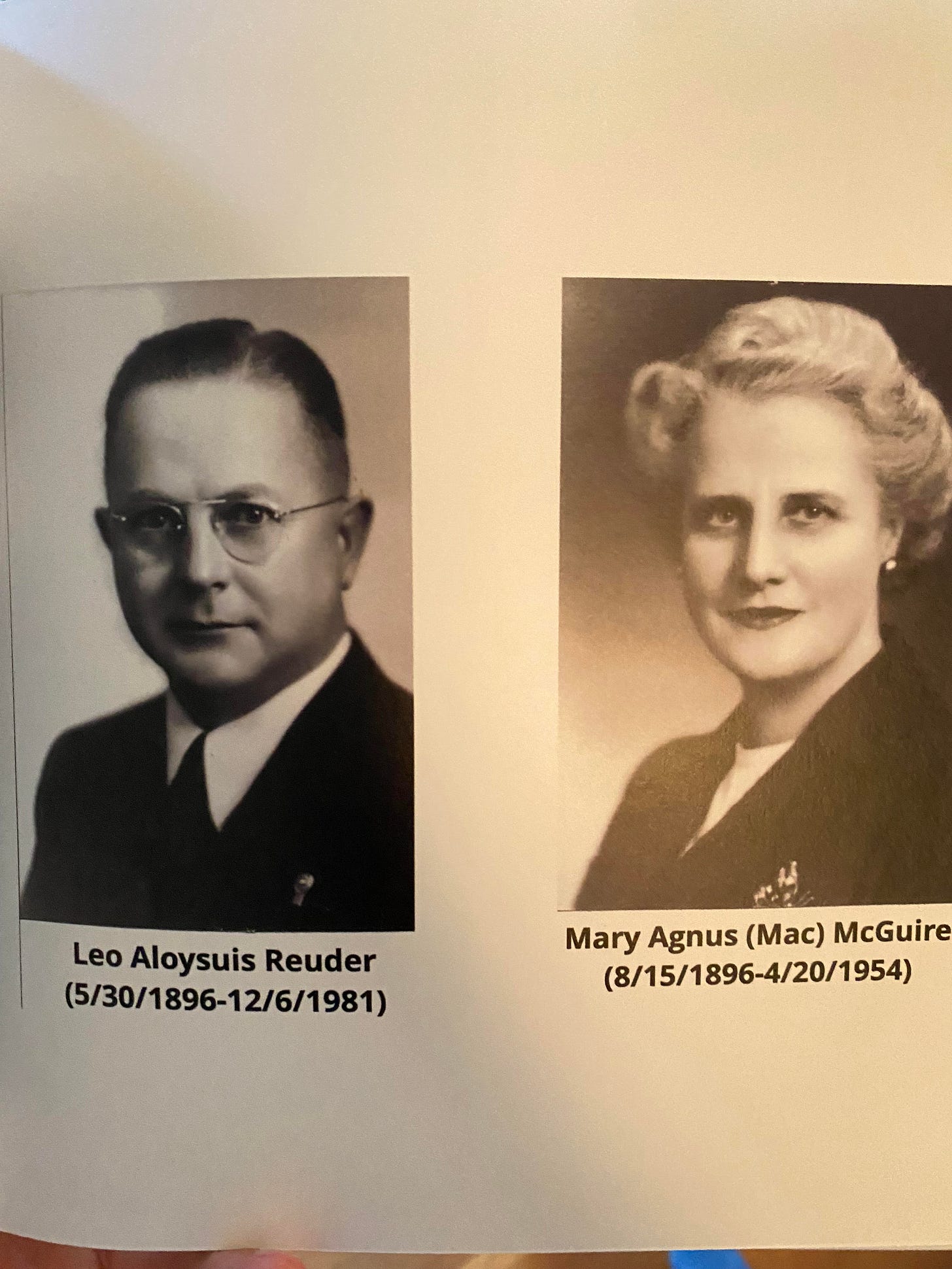

In 1872 John J. McGuire and Winnifred had a son, John H. McGuire. John H. McGuire married another Irish woman named Julia Agnes O’Reilly. They had three children: John Henry McGuire, James John McGuire, and Mary Agnus McGuire, my great grandmother. The McGuires may have been creative in other parts of their lives, but clearly not when it came to naming their boys.

Minneapolis was a cozy home for the McGuires’ enormous Irish Catholic family, but not all of them stayed there. Mary’s daughter, my grandmother Winnie, eventually moved West to sunny San Diego.

“A lucky place to end up for a Minnesota gal like me,” she’d always tell me, seated beside her pool beneath the shade of a lemon tree.

Before leaving the Museum of Irish Emigration I stopped in the gift shop and bought a few coasters depicting the coat of arms of the Irish branches of my family.

The O’Reilly family crest features two lions flanking a bleeding hand, which symbolizes faithfulness, sincerity and justice. The lions signify bravery—Reilly means valiant in Gaelic. Beneath this heraldry is a Latin motto that translates to “fortitude and prudence.” Going forward, I’ll be sure to use this to explain my cautious driving, rebranding it as part of my ancestral calling to be prudent on the road.

The McGuire family crest depicts a knight on horseback with a Latin motto that means “justice and fortitude.” Both branches of my family valued fortitude above all else. The more I learned about Irish history, the more I understood why.

The city I grew up in is named after an Irish philosopher who never visited California. Allegedly, while standing somewhere near what is now UC Berkeley, a group of men, including Frederick Billings, watched two ships sailing out to sea through the Golden Gate channel and recalled the George Berkeley quote “Westward, the course of empire takes its way.”

There’s a lot to dislike about Berkeley, including this quote, but I still believe there’s more to love. Whether the weather lands in the love or hate column depends on whom you ask. Berkeley rarely gets hot. It also rarely stays sunny for long. We’ll get glorious glimpses of full sun, only to have fog, wind, and clouds chase the warmth away every morning and evening like an overzealous sheepdog.

It shares that much with Ireland, I thought, as I wandered into the garden. That must be why potatoes love it here. I’d try to grow dozens of things in my Berkeley backyard and most had ended disastrously. The stunted cayenne peppers longed for more sun. The Virginia peanuts were dug up and devoured by squirrels. The doomed kale was overtaken by an armada of aphids. Somehow, the potatoes persisted season after season. My most recent crop of Adirondack blues had been a colorful success.

Surveying my vegetable beds, I wondered what the O’Reillys and McGuires would say if they saw me planting potatoes in Berkeley. Would they be proud? Would they shake their heads in disbelief? Would they smile? Would they laugh at this blonde boy undertaking mediocre feats of boutique agriculture?

So much depended on their potato harvests.

So little depends on mine.

Potatoes likely helped send John J. McGuire across an ocean, and set in motion the familial saga I’m benefitting from today. As a privileged white person, my Irish ancestry sometimes feels like my only legitimate connection to an interesting cultural heritage or genuine struggle apart from the bland beige stew of whiteness. Ever since I’d stopped listening to podcasts in the garden, these were the kind of thoughts that kept me company.

As I dug up my raised beds to make room for new plantings, I was astounded to find even more Adirondack blues buried in the soil. These ones I hadn’t even put there. Last year’s potatoes had somehow re-seeded themselves. The result was a volunteer crop that was even bigger than the initial batch I’d planted.

Justice, fortitude, and potatoes had prevailed.

I just needed to balance valiance with prudence.

As a breeze whispered through the garden, I felt a quiet connection to my roots, reminding me to have faith in the soil and myself.