“Popular belief would have me think that the desert is a bleak and barren place. I have found it to be the exact opposite; alive, beautiful, and filled to the brim with meaning.”

-Journal entry from day 2 of Vision Quest, March 2008

Into the Desert

When I was 17, I spent 3 days and nights alone in Death Valley.

It was part of a high school program called Vision Quest—a holdover from Marin Academy’s hippie past.

While the school was already well on its way to becoming a hyper-expensive, competitive college prep machine, some of its weirdness still remained. Minicourse was the clearest example, a week each spring when students left campus for some kind of educational adventure—anything from learning to write songs in Marin to scuba diving off of Catalina Island.

Vision Quest was the most exclusive—and to me, most intriguing Minicourse offered. Only juniors and seniors could apply, and it was the only program that required an essay. They wanted to know you’d take this rite of passage seriously. My friend Matt, who’d done it the year before me, told me to include a Thoreau quote in mine. I’ll never know if that’s what got me in—but it worked.

In my essay, I wrote about needing space and silence to see myself clearly. Back then—maybe even more than now—I was churning inside, constantly, anxiously. But I had almost no self-awareness about what was going on in my head, much less why, just a vague sense that I needed a break from—whatever this was.

I hoped that the desert would give me such a break.

I saw the silence of Death Valley as a chance to finally calm down, slow down, and listen.

I projected my deepest hopes onto the blank canvas of the adventure ahead.

Preparing for this journey gave my unmotivated senior brain something meaningful to look forward to—more than just studying for tests. First I assembled my layers: Under Armour pants and short sleeves for the day, a 700-fill North Face down jacket for the cold desert nights. Then I went to the West Berkeley REI for the obligatory survival gear: emergency blanket, whistle, and a compass.

Some of my classmates planned to fast during their solos. I become a monster when I’m hungry, so that was never on the table. If I was going to have epiphanies in the wilderness, I wanted them to be from genuine insight, not hypoglycemia. I compared notes with Tonio, who was also not fasting. His parents had packed him artisanal cured meats from Café Rouge. I went for lighter, but still calorie-dense stuff: nuts, jerky, apples, and tangerines.

I packed a few things purely for fun: a block of soapstone from my dad to carve when my hands got restless, and a Moleskine notebook to capture whatever thoughts showed up in the silence.

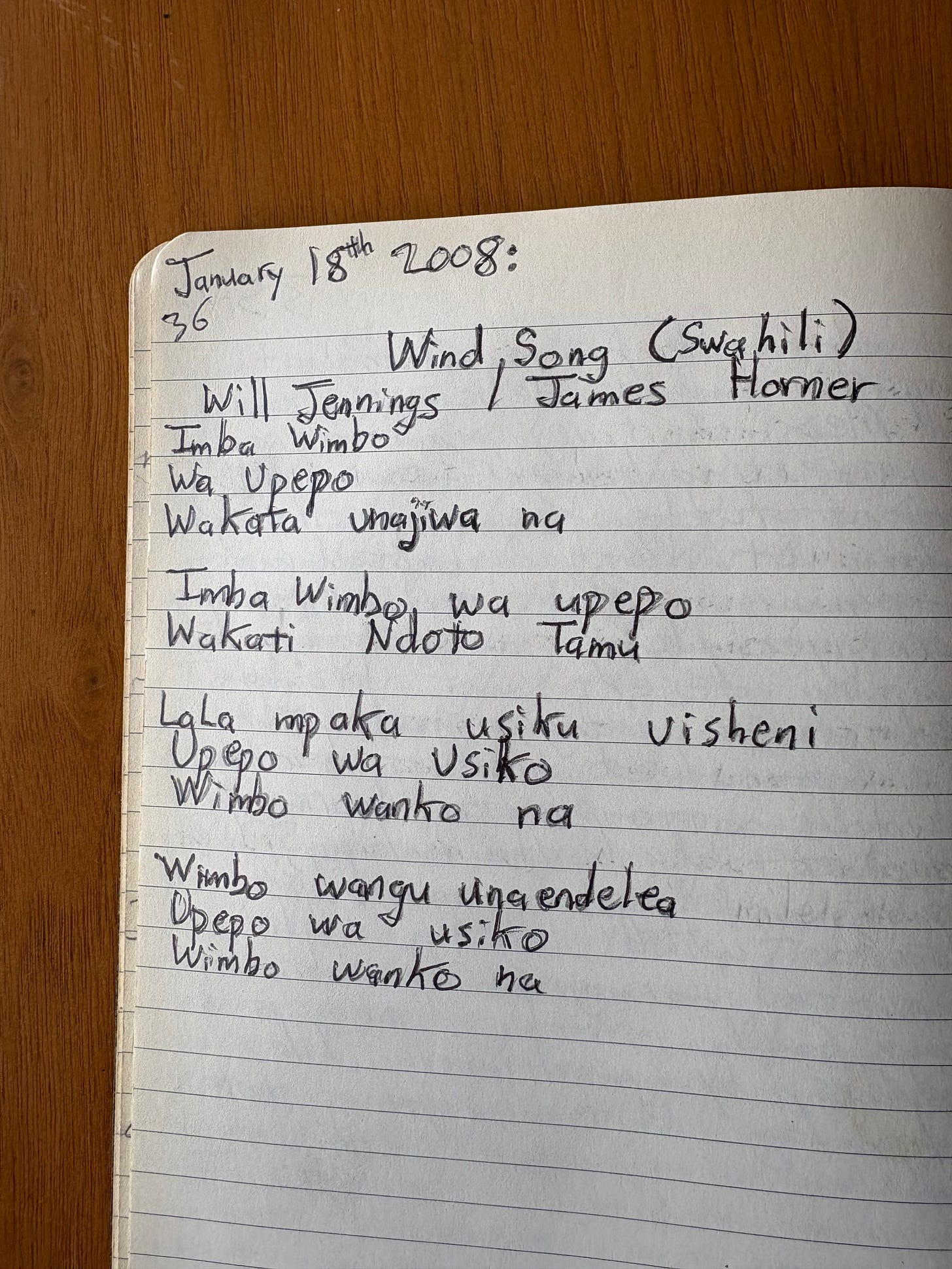

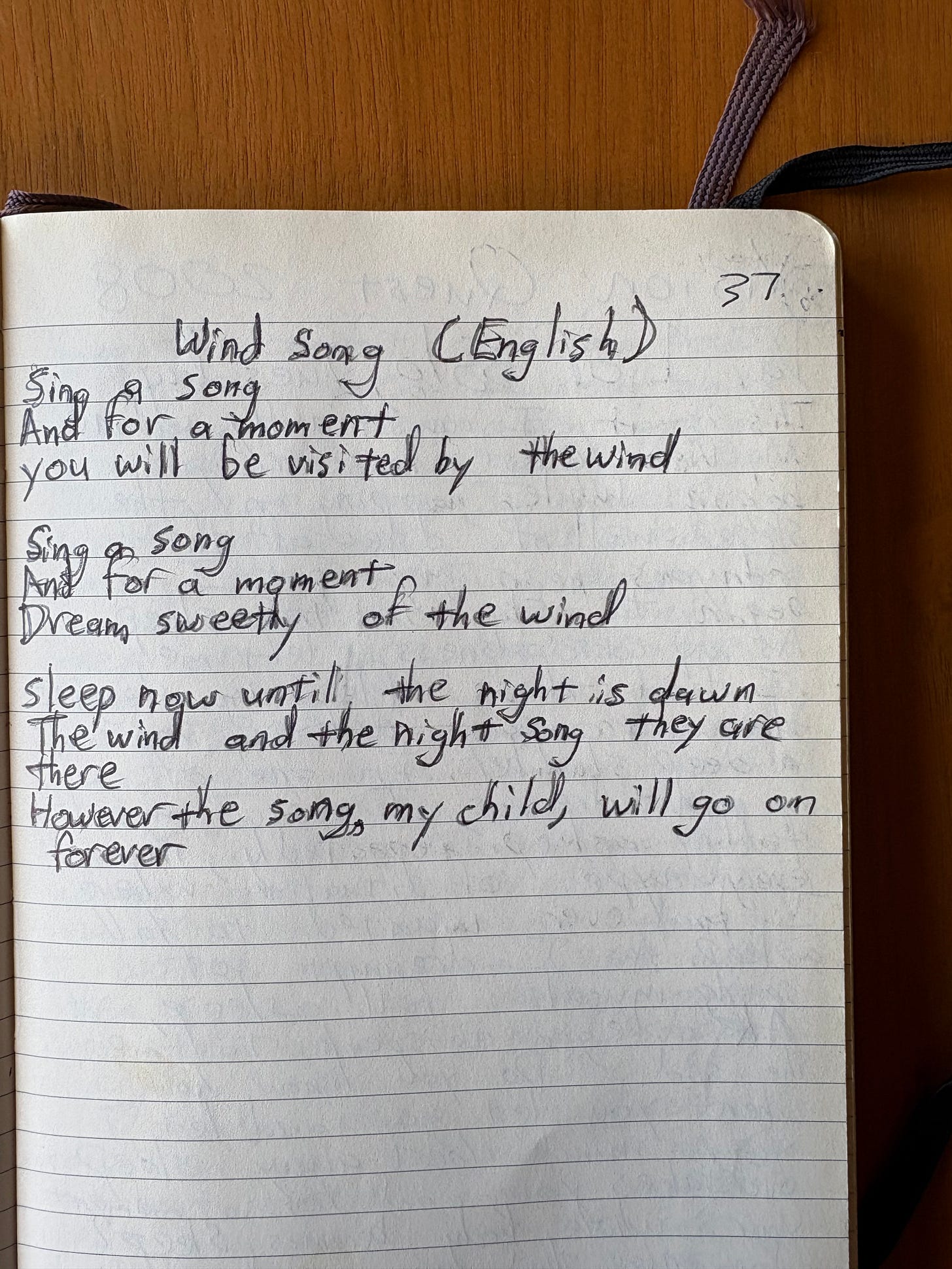

Two months before I left, I opened this journal and wrote down the lyrics to a song I had stuck in my head. I wasn’t sure why—but I knew I’d need it in the desert. It felt like a small act. I didn’t yet know how much it would carry me through Death Valley and beyond.

Mighty Joe, Minor Key

The first time I saw Mighty Joe Young I was in middle school, channel surfing with only a frozen pizza for company when I stumbled across it on the Disney Channel— and cried.

Rewatching it today I’m sure I’d see the flaws, but to be honest, when I first saw it I was convinced it was a masterpiece.

Mighty Joe Young can be charitably described as a decent creature feature—a more hopeful retelling of King Kong, with some melancholy moments and earnest, if clichéd, ecological themes.

The premise is that Jill Young and her mother Ruth are studying gorillas in Central Africa when they find a baby gorilla and name him Joe. Then poachers arrive—killing Joe’s mother and fatally shooting Ruth. Ruth dies, and Charlise Theron as grown up Jill follows in her mother’s footsteps—reuniting with Joe, now a 15-foot-tall adult gorilla. Jill must protect Joe in a world intent on confining and killing him.

Looking back, the best part of this box office bomb wasn’t the story—it was the soundtrack. As Ruth dies, she sings a Swahili lullaby to her daughter to comfort her. It’s sung again at her funeral, and later by Jill to calm Joe. The full version plays over the end credits.

James Horner, the composer of this song, captured a rare duality in it: the tenderness of a lullaby and the rousing, Amazing Grace-style spirituality of an elegy. The lullaby is gentle and soothing, but the choral version is soul-piercing and gives you goosebumps.

It’s devastatingly effective—even if it’s not entirely original.

Hans Zimmer used Swahili vocals to Oscar-winning effect in The Lion King.

Years later, Christopher Tin’s Baba Yetu from Civilization IV, a Swahili version of the Lord’s Prayer performed by the Soweto Gospel Choir—became the first song from a video game soundtrack to win a Grammy.

Soon after I saw the movie it appears in, my Russian music teacher, Yulia, had us learn Windsong in class. I still remember her coaching us how to sing it properly:

“When this song comes back in the movie, it’s at a funeral. You’ve really got to feel the emotion—full force.”

Singing it out loud etched the melody into my psyche. It was my first visceral experience of music as a release valve—as something that could carry grief, then let it go.

This stuck with me.

As a lifelong cultural omnivore I’ve long believed that the most meaningful things often hide in the most surprising places. Even a mediocre movie about a giant gorilla can deliver something transcendent.

If that’s not a metaphor for high school—and life—I don’t know what is.

Discovering “Windsong” nourished a nascent belief I still hold: that songs, like people, enter our lives for a reason.

Every one has something to teach us.

We just have to listen.

Alone, Together

What excited me most about Vision Quest—and terrified me just as much—was the same thing:

Three unstructured days alone with nothing but the sound of my own thoughts.

Thankfully, the trip was well-designed. It began with a series of pre-trip meetings. Vision Quest was more rite of passage than wilderness adventure and our leaders cared as much about emotional growth as logistics.

Long before packing lists were distributed and safety briefings repeated, we spent a lot of time sitting in a circle discussing what brought us to the desert. I was astounded by the stories that people started sharing. Classmates I thought had it all together shared things I’d never imagined—messy breakups, absentee dads, alcoholism at home.

Even more surprising was when the talking stick came to me. Before I knew what was happening, I was opening up about my parents’ divorce. This was a first. There were close friends like Tonio and Sam in that circle who I’d never told about the basic facts of what was going on at home, much less how they made me feel. I’d been so silent on the subject that my friend Brandon had to ask, point blank, why my dad was never around.

The moment the words left my mouth, I felt a lightness, followed immediately by the kind of acidic self consciousness that ate away at me for most of high school: was I making too much of all this? Is a divorce as bad as an alcoholic or absentee father? What if people judged me?

I tried to quiet these doubts as I counted down the days until we left for Death Valley.

After driving all day and most of the night, we finally arrived. We set up basecamp in the Red Amphitheater—a dry river wash between Furnace Creek and the Funeral Mountains, not far from the Nevada border. We’d have a few days there as a group to get oriented. We spent our days doing hikes to scout out where everyone would be setting up their solo spot and spent our nights singing Joni Mitchell and Cat Stevens songs around the campfire.

Then one morning, the big day came. I climbed over the ridge south of basecamp and, after a few miles, set my backpack down at the gentle plateau I’d chosen.

I looked around, giddy—I was finally alone.

I went down into the canyon below and wandered around.

I took in the surprising amount of life all around me: pink-tinged barrel cactuses, birds riding thermals, lizards doing push-ups in the sun that I kept interrupting with my loud, clumsy footsteps. An impossibly tall and snowy peak towered above me, keeping watch over my little ravine.

As the novelty of solitude faded, I expected to feel free—but instead, I felt profoundly lonely and sad. Then I remembered something that David, one of our guides, had told us: that doing an activity over and over again can help you express pent up emotions.

So, I opened up my notebook, found the lyrics of “Windsong” and decided to start singing it to myself. I sung the Swahili part and then read the English part aloud, like a parent singing a lullaby and then reading a story to their baby before they fall asleep. But when I got to the English translation, I started sobbing—suddenly, uncontrollably.

Surprised, but undeterred, I kept going. I began to sense this was why I was here. So I kept singing the song and reading the lyrics aloud, getting louder and louder each time, before basically screaming the Swahili and English into the canyon.

Only then did I stop crying.

As my tears dried, clarity arrived.

This sadness wasn’t just about my parents, or the desert, or even being alone. It was about realizing, for the first time, that part of being an adult means learning how to comfort yourself. I was making peace with the knowledge that, on some level, you’re always alone. To be both the scared child and the one singing the lullaby—that, I realized, was what growing up meant.

Just as clear was the fact that no one was going to tell me how to spend this time or how to make the most of it— I was going to have to decide.

The main thing I was there to do was get to know myself so I could be comfortable with whoever this person really was.

Thankfully, the setting was perfect for this. For the first time ever I could truly hear myself think. With no one around and nothing to do I was able to truly inhabit my body and mind. The serenity of the desert let me exist in a gentle, patient, curious state that I’d never been able to access before.

I was amazed how, without distractions, epiphanies leapt out at me like overzealous dolphins. I had my journal with me constantly and would often pull it out to write them down.

I wrote pithy little musings like these:

“When you walk somewhere you don’t necessarily need a plan or a destination, you just need to keep your eyes, mind, and heart open.”

“If an idea can roll around in your mind for a while and gather more ideas, then it deserves to be written down.”

“I confuse many longings in my life for hunger. I eat when I feel sad, lonely, bored, tired anxious, etc. Out here the desert fills up a part of me that is too often empty so I eat little. I am amazed by the amount of hiking I can do powered only by a few nuts and an apple.”

“Even if you try to fight it, you can’t escape the fact that there is no shade at noon.”

“Tears are just another liquid your body needs to get rid of.”

In my less profound moments, I wrote entries like these:

“I smell like body odor and tortellinis and I’m damn proud of it.”

“In a dream, Mitt Romney told me that one of his most important campaign issues was barbecue. He said that if I barbecued my favorite waffle it would be delicious. No wonder he didn’t win the Republican nomination— he’s nuts!”

The biggest realization from all my hikes, meditations, and journal scribbles was this: I had spent most of high school acting and it was exhausting.

I was tired of acting like I was happy, like everything was okay, like I was invincible, like my feelings didn’t matter, like getting people to like me was a matter of life or death.

I realized just how much I craved other people’s validation to the point where I felt like I constantly had to perform only the most entertaining, intelligent, and charming version of Reilly.

This led me to journal entries like this:

“I need to recognize my worthiness and value to remedy my insecurity instead of trying to prove my worthiness to others. I have nothing to prove or demonstrate to anyone. My friends love me for who I am and I don’t need to constantly try to “win them over,” they already like me. I need to be humble always, like I am in the desert. My ego is not a weapon against insecurity, it is a weapon of insecurity.”

As the first day came to a close, I felt a burgeoning sense of peace, with this place, but also with who I was and what I needed to do.

I also created some routines to stay grounded and entertained.

The first night, just before sunset, I decided get naked while singing “If You’re Into It” by The Flight of the Conchords. Then I put on my long underwear and puffy jacket and hiked up to the ridgeline. As the sun set I howled like a wolf. Then I waited—and heard a chorus of howls coming back over the ridge-lines, from similarly lonely teenagers in distant canyons.

Maybe I wasn’t really alone after all.

Later, I lay on my tarp, nestled in my sleeping bag, looking up at the sky. I was in awe of the sheer number of stars I could see overhead, intermingled with planes coming and going from Las Vegas and the odd satellite patiently creeping by like a celestial snail. With the stars encircling me like a cozy quilt I felt safe to close my eyes. I wasn’t sure when the stars ended and my dreams began.

The two days that followed were glorious. Everything I saw seemed poignant, laden with meaning, dripping with lessons that I thirstily drank in.

Losing a bandana and my sunglasses became a lesson about my vanity and letting go of worries about how I looked.

Watching a colony of ants snack on trail mix I’d dropped became a reminder of the importance of patience, persistence, and teamwork.

Worrying about rainclouds was a metaphor for being prepared and making peace with things I can’t control.

After scurrying about the valley floor like a purposeful ant and scrambling up rocky ridglines like a curious mountain goat, I’d pause to sip some water, have a snack, and scribble more realizations in my journal. I felt like a Southwestern Thoreau.

Every sunset I’d get naked, sing, and then hike up to the ridge to howl.

The indifference of my surroundings remained a constant reminder of how small I was, but now it filled me with gratitude instead of fear and loneliness. Living three days vibrantly alive in such a desolate environment made me realize what a precious gift every day was.

By the morning I knew it was time to hike back to base camp I felt calm, centered, and ready. Having spent three days silent except when I was singing, crying or screaming, I now felt brimming with things I wanted to share with other people.

Teri, one of the leaders of the trip, took photos of everyone as they arrived back at basecamp. More than the anime character hair from days without showers, and the dust and sun altering everyone’s skin tones, the reason she snapped our pictures was to capture the look on everyone’s faces.

I can still remember mine. There was a peace, joy, and love in that 17-year-old man’s eyes that warms my heart even now that I’m twice his age.

The rest of that day of reunion was a joyous, loving blur. We all gathered in a circle and shared hugs, a fruit salad, and stories. For classmates who had been fasting and people like me, this fruit tasted like the sweetest thing we’d ever eaten.

Over a fire, we shared black bean soup and people sang more songs. I told everyone about the windsong keeping me company and then shared it with them. Afterwards, I still felt a little self-conscious. Was it weird to insist on sharing it with everyone? Was my voice terrible? But beside that insecurity was something new: a quiet, calm sense that this, too, was part of me. And that was okay.

Then we settled back into the classics. Better than singing alone was the feeling of singing as a group. No one could get enough of “Angel from Montgomery.”

Just give me one thing

That I can hold on to

To believe in this livin'

Is just a hard way to go

From “Windsong” to “My Heart Will Go On”

James Horner, the man behind “Windsong,” was born in Los Angeles in 1953. He started piano at five, fell in love with Prokofiev and Stravinsky, and eventually earned a PhD in music composition from UCLA. He got his start scoring low-budget B-movies for New World Pictures.

His big break came with Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, and from there, he scored over one hundred films—everything from The Land Before Time and Braveheart to A Beautiful Mind and Avatar. Even in the flops, Horner had a gift for translating raw emotion into melody. He could make strings mourn, choirs ache, and wind instruments whisper with nostalgia.

“Windsong” from Mighty Joe Young is a testament to that gift—a track that transcends the film it came from. Like John Murphy’s “Adagio in D Minor” from Sunshine, it now lives a second life beyond its original context. It’s Horner at his most tender and transcendent—a lullaby and an elegy at once, a song for comforting a child, and for saying goodbye.

But to most people who aren’t movie score nerds like me, Horner is remembered for something bigger: Titanic.

That score is a masterclass in emotion-first storytelling, and its packed with Horner’s hallmark touches—sweeping melodies, Celtic instrumentation, and those ghostly, wordless female vocals he loved. It’s one of the only major film scores to spotlight Uilleann pipes and penny whistles—odd choices that somehow make the music feel both epic and intimate.

What’s most remarkable about the Titanic score is that the song it’s most associated with, “My Heart Will Go On,” almost didn’t happen. James Cameron initially didn’t want a ballad, so Horner composed it in secret, working with Will Jennings on the words and recording a demo with Celine Dion. When Cameron finally heard it, he relented.

Horner was right. Cameron was wrong. The song topped charts, became a cultural phenomenon, and launched Dion further into the stratosphere. But the emotional resonance of the score—like all of Horner’s best work—was no accident. It was the product of decades spent refining a singular skill: crafting music that could carry grief, memory, and longing better than words ever could.

The Second Solo

You can’t step in the same river twice, but college-me didn’t believe in conventional wisdom—so I tried anyway.

Two years after my transcendent high school trip, I returned to Death Valley with Matt and Eric. It was winter break of our junior year in college, and we made an impulsive decision to ring in the new year back in the desert.

I hoped for a philosophical rekindling of the epiphany-fest that was my original solo. It ended up being anything but.

To start, the drive was brutal.

No one else’s parents would lend a car, so I brought my dad’s Audi—a finicky stick shift that only I could drive—for ten straight hours. Right when I thought I’d lose it, we hit the final stretch: three miles of bouncy off-roading over jagged rocks. The car, built for highways, felt like it was reliving the harrowing river-crossing sequence from The Oregon Trail. We were one sharp rock away from disaster.

Then came the weather. Inland deserts get bitterly cold at night, especially in December. Conditions that felt challenging-but-doable in March were dangerous now. We arrived to snow that turned to hail, then sideways wind, then a rockslide.

We spent our first two days huddled around camp playing cards and passing around a thermos of hot water that served as warmth and nourishment all in one.

Desperate to reconnect with what this place had once meant to me, I made an even more impulsive and reckless choice: I’d spend New Year’s Eve alone, in my old solo spot.

I was feeling unmoored—just back from a semester abroad, anxious and full of questions about the future. I hoped the desert might calm me down and provide some answers.

It was foolish. While my first solo was expansive and full of wonder, this one was just cold.

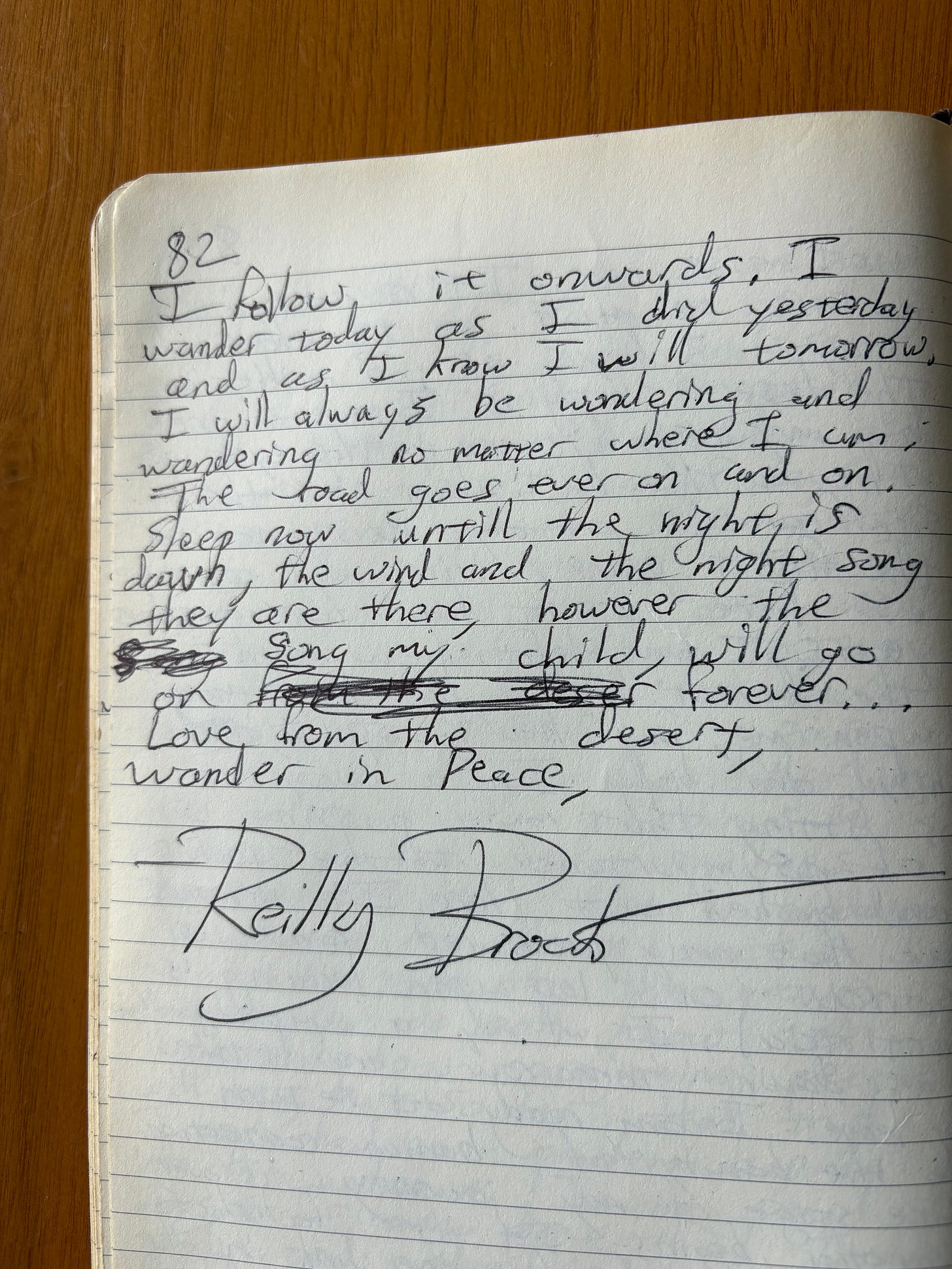

I brought my journal and, before the sun dipped, managed to scribble a few earnest longings like:

“I want to one day be someone’s favorite writer.”

and platitudes fit for a fortune cookie:

“Every day is too precious to worry unnecessarily.”

Then the temperature plunged. I crawled into my tent, layered everything I had, and got into my sleeping bag. It turned out that the only thing colder than winter in Death Valley was winter in Death Valley alone.

On New Year’s Eve, I wrote:

It is too cold to read and too cold to write. I may well spend the transition from 2010 to 2011 lying in a ball in my sleeping bag, thinking, and eventually trying to sleep.

I was right— I barely slept. At first light, I emerged, grabbed my backpack, and hiked to the top of the ridgeline where I knew the sun would hit first.

When it finally rose and touched my skin, I felt a full-body, visceral gratitude unlike anything I’d ever experienced before. I grinned, eating pita bread with peanut butter as the light warmed my face.

Back at camp, Matt and Eric were relieved I hadn’t frozen to death. They told me they’d rigged a water bottle lit with a headlamp-lit into a makeshift ball drop before going to bed. We’d had very different New Year’s Eves.

On our last night, we crossed paths with a group of backpackers who shared their IPAs with us. They were the best beers we’d ever tasted.

When I returned the Audi to my dad, he brought it to the shop and reported that the undercarriage looked like it had been beaten with boulders—and that it was miraculously still attached by only one of its four bolts. It was a miracle we’d made it out there in one piece, much less back.

Still, the final journal entry I wrote on that trip made the freezing, jarring, uncomfortable experience feel oddly worth it:

This will be my task going home: getting better at being uncomfortable, learning to live with discomfort and lack of control in a healthy way. I love myself and believe I have all I need to be happy within me.

As I got ready to return to college, I sat with a quieter, harder truth:

Nature doesn’t exist to hand you epiphanies.

It’s as beautiful as it is indifferent.

You can’t live in a constant state of revelation.

Sometimes, warmth and food are enough.

Sometimes, that’s the revelation.

This, too, is part of growing up: learning that even sacred places don’t deliver on demand, and that you can’t force an epiphany any more than you can force yourself to cry. All you can do is create the kind of setting where the tears—or the insight—might feel safe enough to show up.

The Day the Music Died

James Horner died in a plane crash on June 22, 2015.

He was 67.

Flying low over the Los Padres National Forest, just north of Santa Barbara, he crashed his single-engine Tucano into the Quatal Canyon ridgeline.

Like Patsy Cline, John Denver, Buddy Holly, Otis Redding, and Aaliyah, Horner joined the tragic pantheon of musicians lost too soon to small aircraft.

When I found out he’d died, it felt surreal. How could someone whose music had brought so much light into my life vanish so abruptly?

Listening to “Windsong” felt heavier now. The lyrics, sadder. The final line felt like a whispered prophecy.

Hans Zimmer and John Williams paid tribute to his music. James Cameron and Ron Howard praised his contributions to their films. Celine Dion thanked him for changing her life with a single song.

The world of movies and music spun on. Hans Zimmer won more Oscars, Alan Silvestri opened vineyards, and John Williams continued to compose well into his 90s.

Horner’s melodies still drift through our collective imagination, like haunting echoes from a dream we never want to end.

When I rewatch Titanic, it’s Horner’s cues that move me more than Cameron’s visuals. From the opening “Never an Absolution” to the mournful string quartet playing “Nearer My God to Thee” as the ship sinks, I can chart the emotional contours of Titanic’s melodrama by which instruments are coming and going on deck.

Even the overplayed, parodied, and maligned “My Heart Will Go On” still cuts deep when heard in context—not as a pop ballad, but as a musical meditation on memory and loss. Like much of Horner’s work, it suggests that while life ends, love remembered endures—that music, like memory, can transcend mortality. It’s beautiful and unbearably sad—the kind of ache you carry quietly, long after the credits roll.

But I don’t find myself re-listening to “My Heart Will Go On.”

Since I jotted the lyrics in my Moleskine on January 18, 2008, “Windsong” has stayed with me—on frigid nights and sunny mornings, through heartache and healing.

When I listen to it now, I still feel the canyon walls cradling me like a baby. I still see my tears fall into the dust, like something sacred returning to the earth. I still remember the feeling of comforting myself for the first time.

The lullaby hasn’t aged or faded. It’s still alive in me.

When I hear it, I remember:

Sing a song and for a moment you will be visited by the wind

Sing a song and for a moment, dream sweetly of the wind

Sleep now until the night is dawn.

The wind and the night song, they are there.

However the song, my child, will go on forever.

Beautiful soulful piece Rei! Loved reading it.

Love this.