Treebeard Roars

Why the most cathartic scene in The Lord of the Rings is in the second movie

“The old world will burn in the fires of industry; the forests will fall; a new order will rise. We will drive the machine of war with the sword and the spear and the iron fists of the orc. We have only to remove those who oppose us.”

-Saruman, The Two Towers

“It is a grave error to imagine that the world is not preparing for the disrupted planet of the future. It’s just that it’s not preparing by taking mitigatory measures or by reducing emissions: instead, it is preparing for a new geopolitical struggle for dominance.”

-Amitav Ghosh, The Nutmeg’s Curse

“Wild awe returns us to a big idea: that we are all a part of something much larger than the self, one member of many species in an interdependent collaborating natural world. These benefits of wild awe will help meet the climate crises of today should our flight from reason not destroy this most pervasive wonder of life.”

- Dacher Keltner, Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life

My precious trilogy

The magnetic staying power of the original Lord of the Rings films is defined by a once-in-a-generation perfect storm of intersecting positive attributes. Loyal fans like me take any excuse as an opportunity to hop on our soapboxes and explain these qualities in worrying levels of detail. To start, this magical trilogy occurred at a golden age of cinema, when CGI was good enough to be empowering and impactful but still had to be used sparingly. The result was an artful, collaborative, and astoundingly thorough approach to the source material. Peter Jackson and his army of collaborators chose to interweave practical effects, miniatures, computer graphics, prosthetics, costumes, scale camera trickery, and the natural beauty of New Zealand to bring Middle Earth so vividly to life that it at times looks like a history documentary. The attention to detail alone is jaw-dropping. In the extended editions special features we learn that they hired dance choreographers to teach the stunt team and extras how the different races would move & therefore fight differently, and how Richard Taylor and the quirky nerds at Weta Workshop spent literal years in preproduction making all of the weapons, models, and costumes before cameras even started rolling. Jackson’s filmmaking is playful, energetic, and loving. Even the cinematography is electric, with the camera swooping around the scenery of Middle Earth, giving us an up close and personal tour of its gorgeous geography before dive bombing down the sides of buildings like a Peregrine Falcon with a GoPro.

It’s also a masterclass in adaptation. With very few exceptions, the script confidently cut the perfect things from the book and fearlessly added in new material where necessary to make the story flow properly as a movie. That alone was a Herculean task. The cast is damn near perfect, making us all grateful that Sean Connery “didn’t get” Gandalf enough to read for the part and that Stewart Townsend got booted from the role of Aragorn at the 11th hour. Add to that a pitch perfect score by Howard Shore, with evocative lyrics sung by vocalists and choirs in Elvish, Dwarvish, and Adûnaic. It’s even packed to the rafters with operatic & iconic Wagnerian leitmotifs for each of the different cultures, the ringwraiths, the fellowship, the Shire, Gollum, and even the ring itself. The result is an ornate, immaculate, and timeless work of art. Yes, it’s true these movies also came out when I was eleven to thirteen and therefore occupy the same irrationally nostalgic shelf as the veal cutlets my mom used to cook before my parents got divorced. It’s just as true that they just don’t make movies like this anymore. They probably never will again.

The older I get, the more I understand that what keeps pulling me back to them is actually not the battles or the special effects or the iconic performances. Yes, Helms Deep is likely the GOAT of movie battles, the successful animation of Gollum literally changed film history forever, and the imminently quotable performances of Ian McKellan’s Gandalf, Viggo Mortensen’s Aragorn, Cate Blanchett’s Galadriel, and Hugo Weaving’s Elrond live rent free in my head forever. However, what really makes me keep rewatching this trilogy is the resonance of the themes.

Fundamentally, for all of the epic scale, these are simple movies about the power of friendship and faith, selflessness and trust, persistence and sacrifice. These themes convey profoundly touching messages about what it means to be alive and to live well. The older I get and the more pain, sorrow, and difficulty I experience and see in the world, the more these fantasy movies about hiking to a volcano to destroy magic jewelry hit home in new and surprising ways.

Friendship, fellowship, and the frailty of men

We experience the themes of friendship, selflessness, and sacrifice first through the titular fellowship. We meet the Hobbits and see that they are living with the same amount of responsibility as college students, a band of care free bon vivants happily crushing brews and getting ripped off pipe weed. Only Sam seems to do anything resembling work, yet even his gardening job looks enviably chill. Over the course of the trilogy the Hobbits must each learn to mature and live their lives in service to causes greater than their comfort and pleasure.

Frodo starts his own arc by volunteering to simply walk into Mordor despite not realizing how this task will consume him physically and emotionally. His early commitment is naive but signals he might be capable of bigger things. By the end of movie one he has seen how Gandalf sacrificed his life to give him a fighting chance and realized the true stakes and isolation inherent to his quest after a heated staring match with Cate Blanchett’s etherial Galadriel. He’s also seen what the ring did to Borimir. This ultimately forces him to grow up and live up to Gandalf’s advice, focusing on deciding what to do with the time that is given to him instead of complaining about all of the difficulties he’s facing. So he steps up and takes full ownership and responsibility for the quest, charting his own path to success over the next two films.

Yet on a thematic and plot level Sam is perhaps the real protagonist of the entire trilogy, doing more selfless, thankless acts for Frodo and his quest than any other member of the fellowship. Sam’s story is a poignant case study in the power of devotion, compassion, and selflessness in pursuit of a common goal. Similarly, Merry and Pippen grow out of the foolishness, clumsiness, and vegetable thievery we see them embody at the start of Fellowship, eventually maturing into selfless warriors fueled by their love of the Shire and their friends. So, by the end of the films when Aragorn says “My friends, you bow to no one" we are so moved because the Hobbits have earned this payoff, both as a collective and individually.

Part of what makes Borimir’s arc so intense and compelling in the first film is how, like us, he struggles with conflicting desires. He is visibly torn between his tomato-chomping father’s sick sense of duty, his earnest desire to help, his people’s peril living on the doorstep of Mordor, and his own human frailty. So when Borimir, like so many before and after him, succumbs to the ring’s power, we can understand and empathize with his failure. When he sacrifices his life to redeem himself and give the Hobbits a fighting chance to complete the quest, we feel the fall of this flawed man deeply.

On top of the individual character level themes are larger, political themes. It’s the different factions of men that act these out on a macro level. In addition to exploring how Elves and Dwarves can learn to trust each other and work together via the microcosm of Legolas and Gimli, Tolkien also has us experience how Rohan and Gondor must learn to trust each other and work together to stand united against Sauron.

Initially, we meet the two leaders of men (Aragorn hasn’t yet ascended) and realize they’re both frail and petty old men whose stubborn stroking of past grievances is getting in the way of good leadership. Theoden of Rohan wakes up out of a Saruman-induced trance to discover that he’s is facing the prospect of utter annihilation at the hands of Saruman’s hordes of Uruk Hai. To respond to this existential threat he has few options. Rohan’s people can only be described as rich if wealth is measured in horses, beards, and blondes, so retreating to Helm’s Deep isn’t really a choice. There he can only hope and pray that walls will serve as a force multiplier for his ragtag band of towheaded equestrians. Yet Theoden’s real deficiency isn’t in men, swords, or arrows, but in his character. This flaw follows him to his fortress. Even holed up in his mighty castle, his biggest vulnerability isn’t the culvert that Saruman eventually blows sky high; it’s his pride and refusal to ask for help.

Theoden’s isolationism and self-pitying approach to war is a doomed one and he’s only spared by Aragorn’s heroic leadership, some Elves that weren’t in the book, and of course the very timely arrival of Gandalf & friends. He learns the hard way that he has to rely on others. Without help from his allies, he would have surely lost. So it’s gratifying later when he puts this learning into action. Seeing that Gondor has called for assistance via (in)conveniently placed alpine bonfires, he responds by showing the generosity he previously assumed Gondor would never show him. When the beacons are more lit than a Coachella headlined by Beyoncé, he changes his ways because he knows from personal experience that the right thing to do is to offer help unconditionally.

Later on in Gondor, we meet Denethor, played by John Noble. His Shakespearean performance of this unhinged and deteriorating mind stops just short of chewing on the scenery and cursing out the audience. More than eating tomatoes like a psychopath and being a dick to his youngest son, Denethor’s biggest flaw as a character is his pessimism and fatalism. He has no faith that Rohan or anyone else for that matter will be there for him in his hour of need. So he’s fully prepared to give up hope at the first sign of trouble. Gandalf challenges Denethor to be more hopeful the way Aragorn challenges Theoden to be more diplomatic. However, unlike Theoden, Denethor doesn’t have a redemption arc. He is instead a cautionary tale, a foil to Theoden’s growth. His tragic downfall shows us the consequences of imprisoning yourself in negativity and self-absorption. After being insufferable to watch, even and especially while snacking, Gandalf and Pippen have to repeatedly foil his plan to roll over in the face of Sauron’s armies. With even his spectacular “I give up” gesture thwarted, Denethor flames out in a vertiginous fall from grace for the ages.

“Nobody cares for the woods anymore”—the ecological tension of Middle Earth

A master of careful and intricate world building, Tolkien doesn’t limit his themes to political squabbles between Medieval lords. Most poignantly, he includes even larger ecological themes with a planetary weight that have only gained relevance with each passing year. Throughout the trilogy of books and the later film adaptations we feel a stark dichotomy between two clashing philosophies about nature. One worldview values industrialization, utilitarianism, and military dominance and the other values respect, love, and harmony with the natural world.

Standing in for the military industrial complex is of course Saruman and his alliance with Mordor. Saruman has a profoundly utilitarian view of the world. All living beings and natural resources are means for him to achieve his end of power. He takes his personal brand of realpolitik to exploitative extremes, chopping and burning all of the nearby trees with a single-minded intensity that makes the orgy of capitalist clear-cutting of The Lorax look restrained in comparison.

In Saruman’s behavior, we see clear echoes of the environmental exploitation inherent to the European colonization of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. In his polemic The Nutmeg’s Curse, Amitav Ghosh describes how before dominating, removing, and killing people, settler colonialism had to first establish an ideology that nature had no agency or purpose other than to be exploited by industry, arguing:

“European perceptions of what constituted a proper use of the environment thus became a European ideology of conquest.”

To the Sarumans of fiction and history, forests, mountains, and rivers have no inherent value, beauty, or meaning. They are only defined by what they can do for us. In this paradigm, perversely we only truly understand nature by destroying it and then consuming it. A forest is understood as lumber, fuel, or paper. A river is understood as something to be drained, diverted, or used for electrical power. A mountain is understood as where to find veins of iron ore, copper, and uranium. Concepts like forests being beautiful, a river being home to rare Salmon, or the gods living in the mountains are not just irrelevant to this worldview, they are a threat to its existence and profitability. The logical conclusion is that dissenting world views have to be removed and destroyed along with their people for industry to triumph.

On the other end of the ideological spectrum are the Hobbits, the Elves, Tom Bombadil, and The Ents. They represent the romantic notion of living compassionately in harmony with nature. This is clearly based on Tolkien’s love of the English countryside. You see this especially poignantly in Jackson’s touching introduction to the Hobbits in Fellowship. Over Howard Shore’s tender fiddle and Irish whistle, we see and feel that the Hobbits live a vibrantly simple rural life proudly defined by how “non-industrious” it is.” If Saruman views the world in instrumental terms, then characters like Treebeard and Sam view it in romantic terms, believing that natural things have a beauty, soul, and even personality that exists independently from what you can extract from them. For them, a life well lived means living in harmony with nature and not imposing on other people, creatures, or ecosystems.

Let’s be crystal clear about one thing. Tolkien hated allegories, famously writing that “I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence.” So this is all not to say that Saruman represents Nazi Germany or Kaiser Wilhelm (Tolkien’s real battlefield foe in World War One, where two of his close friends died and he wrote the first pages of The Silmarillion). Similarly, while the Hobbits are inspired by rural British values, they are not a metaphor for it. Tolkien isn’t interested in the 1:1 correspondence of an allegorical language, but rather building something with a deeper and more timeless resonance. This comes down to the warring ideologies of the warring factions.

In addition to the plot’s central question of who will destroy the ring and how is a larger and more impactful thematic question: which worldview will win out? What kind of world will our protagonists live in if they survive the quest? Will it be the scorched earth capitalism of Sauron and Saruman or the bucolic bliss of the Hobbits and the Ents and their symbiotic serenity with nature? This question gets its first and most powerful answer earlier than you’d expect. While the biggest narrative climaxes occur at the end Return of the King with its bevy of endings, I’d argue the single most satisfying thematic climax is at the end of the second film. You may be able to picture the scene I’m talking about at this point. So why do I get so much satisfaction re-watching talking trees wake up and choose violence?

The moral thrill of Tolkien’s eucatastrophes

Ever a linguistics nerd, Tolkien believed that English needed an antonym to the word “catastrophe.” So he coined the term eucatastrophe, a sudden positive reversal. When things look bleakest, instead of everything falling apart, everything dramatically works out. With this term in mind, the LOTR trilogy is positively packed with eucatastrophes. If you’re not sure what I’m talking about, just think about how many instances a conveniently placed giant eagle swoops in to save the day. Cynical viewers or haters of ornithological storytelling might argue that anytime Tolkien wrote a character into a corner, he’d have an Eagle swoop in to deliver a cathartic eucatastrophe. I can think of three separate “Eagle-Ex Machinas” off the top of my head right now.

While these moments are particularly prominent in the third film, the other two movies have some powerful ones, too. In The Fellowship of the Ring we have of course Gandalf’s timely bird rescue from Isengard, Frodo surviving his encounter with the business end of a cave troll, and Borimir selflessly saving Merry and Pippin from being killed (only to end up as a human pin cushion for Lurtz’s arrows). In The Two Towers the most iconic one is at the end of Helms Deep. We can all recall our gasps of relief when Gandalf’s spectacularly appears on horseback as day breaks, there to literally call in the cavalry and bring desperately needed reinforcements to the overwhelmed fortress by skiing their horses down that black diamond slope. There’s no cinematic release of tension quite like it. It also got a hilarious satirical treatment after the 2020 election:

We love Tolkien’s eucatastrophes because we all desperately want to believe that our own struggles and suffering aren’t insignificant. We need to think that they matter and mean something and that maybe, just maybe, our goodness and faith will be rewarded with victory in the end. If this sounds religious, it’s because it is. Tolkien was, it should be noted, a devout Catholic. You can see explicitly Catholic imagery in huge chunks of LOTR, like the resurrection of Gandalf, the Grey Havens as an afterlife, and the overall emphasis on faith and moral purity to get a “just” ending to your story. Yet these themes also land for non-Catholics and even atheists. Like organized religion, good stories can help deliver this rare and necessary kind of transcendence and absolution. As famous Youtuber, fellow essayist and kindred LOTR nerd Evan Puschak writes in Escape into Meaning: “My obsession with Lord of the Rings, what drove me to watch it fifty times (so far), doesn’t speak speak to a secret desire for religion, but to a peculiar feature of the human mind: its craving for meaning.”

The last march of the Ents

While Gandalf’s triumphant charge at Helm’s Deep resolves the primary plot and political tension of The Two Towers, it’s intercut with another scene that resolves the thematic tension of not just The Two Towers, but the entire trilogy. We arrive at last to the last march of the Ents.

After an agonizingly slow and bureaucratic debate amongst the Ent-moot that makes our own congressional representatives’ decision making look as speedy as Usain Bolt, ever patient Treebeard reaches an unexpected breaking point. Thanks to some deliberately bad directions from Pippen, Treebeard discovers that Saruman’s orcs have devastated his home of Fangorn forest. In response, he roars with rage and decides to go to war on the spot. What follows is one of the most cathartic sequences in all of cinema for me. Watching him and his friends trash Isengard delivers a rush of emotions beyond almost anything else I can think of. Every time I watch that scene, accompanied by the hauntingly beautiful score by Howard Shore, I get goosebumps. Why is this moment so satisfying? What does it say about me and the world I live in that my deepest desire for over twenty years has been to see some talking trees beat the shit out of a wizard and his monstrous army of amateur loggers?

Situating ourselves in the film is a helpful starting point. Things feel truly doomed by this point in The Two Towers. Theoden and company look like they’re about to be slaughtered in battle by Saruman’s overwhelming number of super soldiers. Frodo is imprisoned by Faramir in waterlogged Osgiliath, with orcs and wraiths closing in around him. Most importantly, that treacherous wizard Saruman has been winning basically unopposed this whole time. We the audience object to his naked lust for power and his vile treatment of other men, wizards, and trees. Yet he has yet to suffer a single negative consequence for his greed, scheming, and rush towards militarization. We begin to wonder if Saruman the White will escape accountability entirely, like the white collar criminals of our world.

In this narrative context, Treebeard’s surprising decision to attack Isengard is exactly the eucatastrophe we’ve been craving. When the last of the Ents stride stoically towards Isengard after he says “It is likely we go to our doom,” you want to stand up and cheer. It’s the same rush of gratification you feel when the Elves show up (apocryphally for book fans) before Helms Deep, or when the Fellowship makes it off of that crumbling staircase in Moria. Finally, some good news! We’re so thirsty for some hope that we chug this new development in one gulp.

The last march of the Ents is also a satisfying character moment. When Treebeard finally takes decisive action and steps up to defend the downtrodden forests, it means a lot because it requires his character to finally change. When Merry and Pippen first meet Treebeard (voiced spectacularly by John Rhys Davies aka Gimli) he is not warlike or even emotional. He is patient and cautious. He views the world with a stoic detachment the way your overly thoughtful grandparent might. Like a grandparent, he feels increasingly forgotten about and irrelevant, answering Merry’s question of whose side he is on by saying: “Side? I am on nobody’s side because nobody is on my side. Nobody cares for the woods anymore.”

This sad resignation leads to his own brand of isolationism. Like Theoden, Denethor, and even the Hobbits at the start of the trilogy, Treebeard believes that he has nothing to gain from getting involved in the geopolitics of Middle Earth. So he retreats and attempts to be the Switzerland of the region. While he’s located in the heart of a warzone, Fangorn sitting smack between the rival factions of Isengard and Rohan, he is geographically isolated enough to ignore it. The intertangled branches of Fangorn Forest is to him what the jagged, impassible spires of the Alps are to Switzerland. This careful characterization and larger political context within the world makes his eventual decision to go to war with Saruman that much more satisfying.

As an anthropomorphized representation of the forest, Treebeard’s actions have a deeper symbolic power as well. In the storming of Isengard, we see nature finally fight back. Seeing trees take revenge against industrial exploitation is a glaring contrast to the world we live in where nature gets literally bulldozed everyday without most of us batting an eyelash. Indeed, as Ghosh writes, our worlds capitalist ideology is based on:

“The assumption that planets are inert; that they have no volition and cannot act that they exist only as resources to be used by those humans who are strong enough to conquer them.”

If you think Ghosh’s writing is too dry or academic, consider that this same thesis is front and center in “Colors of the Wind” from Disneys more problematic-by-the-second Pocahontas: “You think you own whatever land you land on/ The Earth is just a dead thing you can claim/ But I know every rock and tree and creature/ Has a life, has a spirit, has a name.”

I bring up Pocahontas not because it’s a great movie or an accurate depiction of anything, but to illustrate how very common this narrative shorthand of embodying nature through one character or group of characters is. It’s ubiquitous because it’s effective. Characters like Treebeard, The Lorax, Pocahontas, and the Navi in the Avatar speak to us because they give a name and a face to a natural landscape that’s viewed by other characters (stand ins for our politicians and corporate overlords) as an inert and soulless mass of exploitable resources. In this way, Treebeard operates as an unexpected leader of the resistance, there to swing an axe back at the loggers.

We instinctively root for him because in our world we don’t get to see nature fight back very frequently, much less successfully. So we long for a world where carelessly destroying nature has meaning and therefore consequences. Additionally, our reference points for what environmental progress looks like are so slow and incremental that seeing such a quick and decisive win for nature hits much harder. If modern environmentalism looked like the Two Towers, we’d witness scenes like Al Gore singlehandedly stopping the Deepwater Horizon spill or Greta Thunberg roundhouse kicking Joe Manchin. This fantasy scene validates our implicit desire for a society where nature is respected, decisive environmental action is possible, and powerful men like Saruman are held accountable.

Giving the forests an anthropomorphic leader also makes you see Saruman’s militarism in a new light. What Saruman has done clearly upsets Treebeard on a deeply emotional, political, and moral level. We hear this in his heartbroken dialog: “Many of these trees were my friends. Creatures I had known from nut and acorn. They had voices of their own…A wizard should know better. There is no curse in Elvish, Entish, or the tongues of men for this treachery.”

But more than that, we feel it in the angry, anguished, and iconic roar he bellows out into the universe. This uncharacteristic fury speaks to the scope of Saruman’s betrayal of the natural world. Seeing things as we do from Treebeard’s perspective, Saruman has basically committed genocide, exterminating thousands if not millions of his people in pursuit of his agenda of military expansion and geopolitical domination. It’s truly sickening. Treebeard shows us that Saruman has taken industrial rationality to a dangerous new level. He has been so obsessed with the practical question of what he can do that he’s lost all touch with the moral question of what he should do. Treebeard is so furious not just because he’s lost friends, but because Saruman has lost all sense of right and wrong.

So when we cut back from Helms Deep to see the Ents finally storming Isengard, smashing orcs, and destroying Saruman’s factories of war, it’s much bigger than a talking tree being angry at a wizard. Watching the cleansing waters of the river Isen flood across Isengard, seeing the water wash away Saruman’s destructive empire while the Ents stand firm in the rushing current (and stressed out Beechbone mercifully extinguishes his flaming hairdo in the water) we are given a moment of karma and justice that this film, this trilogy, and our lives all desperately need.

A wizard should know better, but do we?

In the run up to and aftermath of World War Two, a group of sociologists grappled with the thorny question of how Germany, and much of the rest of the world had gone mad. They were obsessed with answering this question: what could possibly explain how Germany, at one point an “enlightened” hub for philosophy and music, had descended into fascism, genocide, and the horrors of mechanized global warfare? Later known as the Frankfurt school, and led by thinkers like Marcuse, Adorno, and Horkheimer, these passionate sociologists spilled a lot of ink on this topic. Some has stood the test of time better than others. Cantankerous contrarian Theodore Adorno insisted on dying on the hill that he hated jazz for a reason that I still can’t understand even after reading multiple essays about it as a sociology major in college. What stuck with was Horkheimer’s 1947 book The Eclipse of Reason, where he explains how Nazi Germany perverted the concept of rationality to a morally reprehensible extreme. He argues that they took the pursuit of industrious efficiency so far out of any moral framework that the ultimate, despicable and horrific question they ended up answering was how to slaughter millions of people as efficiently as possible.

Driven by the thorny question of “what the hell happened to the Germans?” the Frankfurt school powered sociology into a new intellectual frontier, giving it a philosophical “software update” that it sorely needed to remain relevant in the 20th century. Attempting to understand the real life Sarumans and Saurons of their age, they first had to come up with a new vocabulary to describe them. To do this, they began by explaining how the language of scientific rationality had been used to justify both dominating and destroying nature through unchecked capitalism and then dominating and destroying people through unchecked fascism, racism, and militarism. Post-pandemic, writing about the destructive persistence of this problematic worldview, Amitav Ghosh describes capitalist ideology in terms the Frankfurt school would raise a stein to in grim agreement:

“It is a vision in which genocide and ecocide are seen to be not just inevitable, but instruments of a higher purpose”

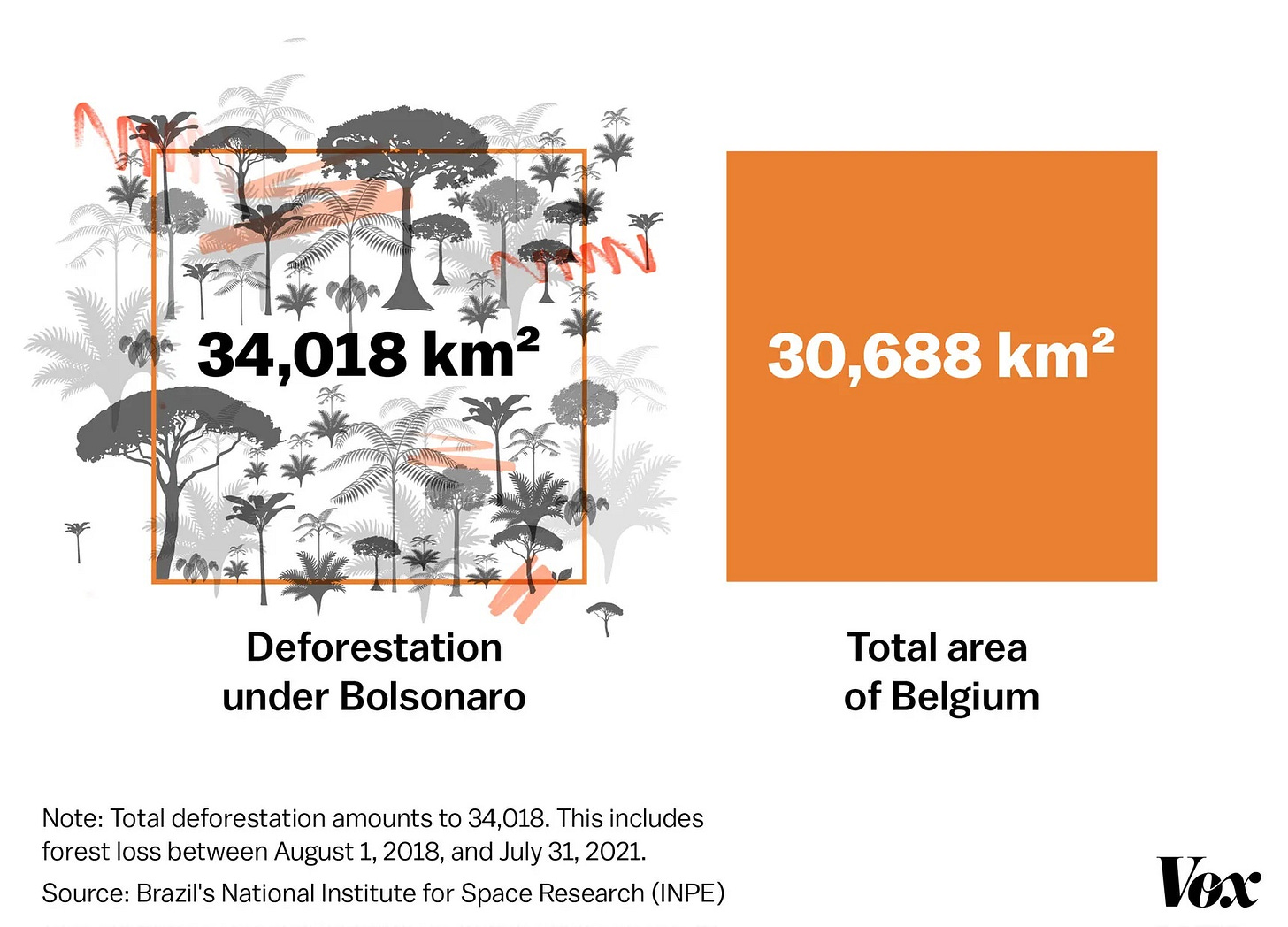

While today the Frankfurt school isn’t widely read outside of sociology curriculums, the questions they were fixated on are probably more relevant than ever. They are at the heart of Brazil’s existential question of what to do with the Amazon rainforest, why the rechargeable batteries in the device you’re reading this on likely contain Cobalt mined under slave conditions in the Congo, and how the “freest” country in the world spends so much money on weapons of warfare.

The Lord of the Rings, is of course not an academic work, much less an explicitly sociological one. We look to fiction like The Lord of the Rings to deliver the kind of hyperbolic resolution that eludes us in both academia and the real world. Yet what makes the last march of the Ents so tragic and beautiful to watch for me is not just the fantasy elements. It’s how much our world today actually resembles Tolkien’s Middle Earth. Despite what Berkeley residents would like to believe, the world we live in today looks a lot more like Isengard than it does Hobbiton. Look at how our species has metastasized into unnatural environments by cutting down mangroves, draining swamps, and damming rivers. Do our concrete and steel cities, Amazon fulfillment centers, and factory farms look that much different than the scarred landscape outside of Isengard? From an ecological standpoint, many of our densest cities are about as out-of-place as Orthanc is. As Ghosh reminds us:

“What Miami, Mumbai, Houston, and Phoenix have in common is that their growth has been made possible by extensive alterations to their surroundings.”

Similarly, real life Sarumans are actually a lot easier to find than you might think. When Russia set out on an agenda to “tame” Siberia, an area that contains one quarter of the world’s total wood inventory, more than half of its coniferous forests and therefore one of the planet’s largest carbon sinks, the justification could have been a speech delivered from the spiky obsidian balcony of Orthanc. In The Tiger, John Valliant shares how Russian propagandists justified this explicitly tree-slaughtering agenda by saying:

“Let the fragile green breast of Siberia be dressed in the cement armor of cities, armed with the stone muzzles of factory chimneys, and girded with iron belts of railroads. Let the taiga be burned and felled, let the steppes be trampled… Only in cement and iron can the fraternal union of all peoples, the iron brotherhood of all mankind, be forged.”

You can almost picture the seething masses of Uruk Hai chanting and bashing their pikes with furious glee. Closer to the present day, just look at what now ousted Brazilian president Bolsonaro did to the Amazon rainforest during his reign under the guise of industrializing Brazil.

In my home state of California, we’ve had droughts and wildfires decimating millions of acres of our forests for the better part of the last decade. Treebeards lamentation that “no one cares for the woods anymore” could just as easily apply to the Russian Taiga, the Brazilian Amazon, or the Sierra foothills of California. Looking around, I can’t help but feel like many of us are actually living in our own private versions of Isengard. Our society looks more like it’s run by orcs than by Ents.

Staring down the slow motion car wreck that is climate change, I’m also struck by the fact that perhaps I’m fixated on the triumph of Treebeard because in modern environmentalism comeuppance and catharsis are scarcer than Cobalt and Lithium. Our world and its conflicts aren’t packaged in the tidy, morally straightforward bundles of Tolkien’s Middle Earth. Forests get clearcut and burned down all the time without any particular consequences at all. On the contrary, people get rich for cutting down forests, damming rivers, and dynamiting mountains. There are whole industries built around these activities and huge chunks of our economy and the financial markets that bet on it daily depend on and encourage this insatiable consumption of nature. So while on an individual level I may object to the Saruman-ization of my world, I not only feel powerless to stop it; I’m actively complicit in supporting it.

Normally mousy intellectual Ezra Klein had his own Entish moment when interviewing a guest on his podcast recently, wondering aloud why environmental terrorism isn’t more common. His argument essentially boiled down to: “Given what we know about climate change, why aren’t why the Greta Thunbergs of the world blowing up coal power plants to stop CO2 emissions?” Put another way, where is our Treebeard?

Well Ezra, in our world, when people fight back on behalf of themselves and nature, they’re often quickly and violently suppressed by the forces of industry. Leaders of these environmental movements are of course not charismatic mega-plants, but often BIPOC activists living on the land threatened by industry who are persecuted, silenced, and oppressed by our governments and corporations. In Nigeria, the Dutch petrochemical company Shell paid the government to violently suppress Ogoni protests to their extractive business practices. In the US, when Sioux activists tried to stop an oil pipeline that would threaten their water supply from being built through their ancestral lands, they faced police with dogs and water cannons, and despite a valiant struggle and national media attention and support from liberals like me, the pipeline was built anyway. In the past decade, over 1,700 environmental activists have been killed in countries like Brazil, Colombia, the Philippines, Mexico, and Honduras.

In non-Middle Earth, nature itself doesn’t really fight back, at least not how Treebeard does. When our nature does its own version of Treebeard’s roar, it sadly catches many innocents in the crossfire. While Treebeard’s vandalism and subsequent flooding of Isengard harms only orcs we openly loathe and their untidy wooden scaffolding, real life examples of mother nature putting us in our place like hurricanes, floods, and wildfires more often than not hit vulnerable communities of color first and hardest. It’s largely innocent people that are killed, injured, and displaced in natural disasters fueled by climate change, not Exxon Mobile executives or BP stockholders. So the dramatic question of the end of The Two Towers persists: who will defend nature?

You might just as easily flip this question on its head and ask, is it nature that needs defending or is it us? When I interviewed community garden legend Ron Finley on my podcast, he dropped many knowledge bombs on me, but one has stuck with me to this day as prophetically relevant:

“Nature always wins. Just ask those people at Pompeii.”

With the weather getting weirder and less predictable by the year, to me it seems inevitable that our planet will experience its own version of Treebeard’s mighty roar. Some might argue we’re already hearing it now. The only real question is when and what it will look and sound like. To respond to this crisis, our governments are more chaotically divided than the council of Elrond and moving with the urgency of the Entmoot. This leaves all of us are left to prepare for it individually, collectively, or not at all. Judging by how humbled the US was by a respiratory virus, I’m not optimistic that we’ll showcase the friendship, fellowship, and sacrifice needed to summit the Mt Doom of our time. Still, that’s no reason to not try and do our best. What keeps me up at night is the realization that unlike the Ents, our nature’s fury will likely be indiscriminate in its violence and indifferent to our moral purity or allegiances. In the face of this kind of wrath, protected by elected officials with the moral integrity of the Nazgûl, fellowship seems like the only defense we have left. Re-watching The Lord of the Rings a few more times certainly wouldn’t hurt though.