“You run to Atlanta when you need a few dollars/ No, you not a colleague, you a fuckin’ colonizer.” -Kendrick Lamar, Not Like Us

Sammie: “You know something? Maybe once a week, I wake up paralyzed reliving that night. But before the sun went down, I think that was the best day of my life. Was it like that for you?”

Stack: “No doubt about it. Last time I seen my brother. Last time I seen the sun. And just for a few hours, we was free.”

In a world of copy-pasted movies churned out by risk-averse studios, most blockbusters now feel like AI-generated Mad Libs:

We’re introduced to a hero (Ryan Reynolds / The Rock / Gal Gadot / Vin Diesel / Jason Statham / Kevin Hart, all just playing themselves), who is witty, hot, and good at everything. They must partner up with (A quippy Chris Pratt/ Pedro Pascal in full daddy mode/ Kirkland Chris Hemsworth/ Michelle Yeoh, who deserves a better script than this) to defeat (a greedy capitalist / an evil twin / a generic military goon) by overcoming (an army of identical gray creatures with zero backstory / a CGI sky beam/ a hopeless amount of dinosaurs/ the multiverse collapsing under its own narrative weight) with the help of (guns / family/ plot armor/ American-made automobiles).

In these dark times for creativity, there’s something electric about seeing a film that feels truly original.

Sinners is that film.

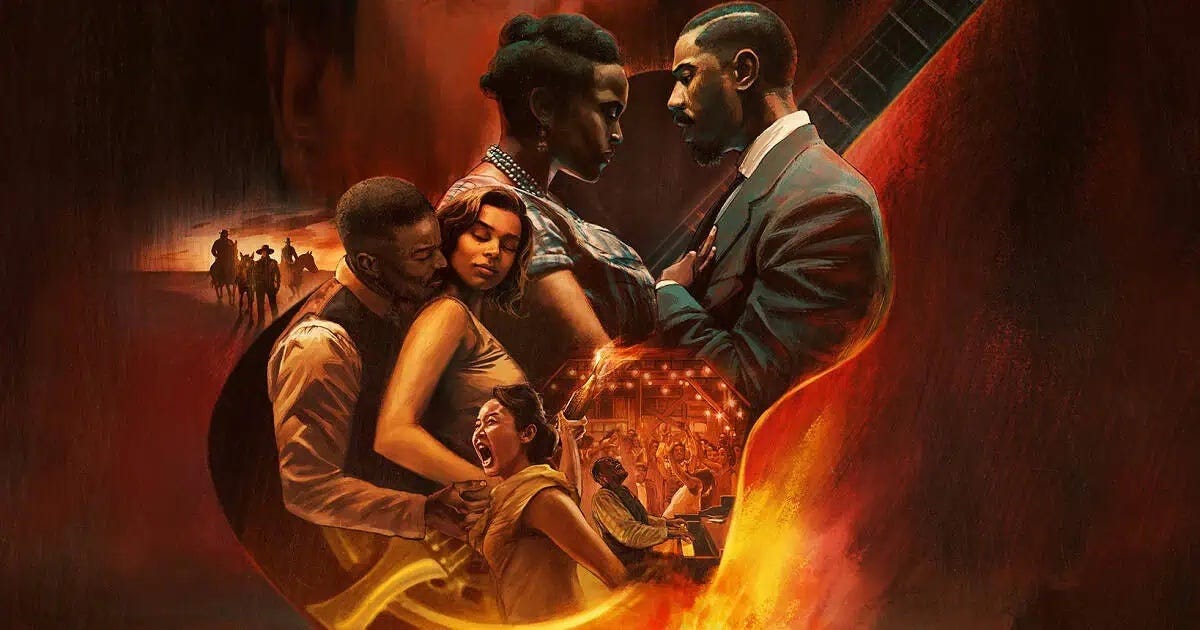

Directed by Ryan Coogler, best known for Fruitvale Station, Creed, and Black Panther, Sinners is a bold genre-blender—a period piece, juke joint musical, and supernatural horror movie all at once. It’s lush, surprising, and deeply rooted in Black history and culture, confident and thought-provoking without ever losing its sense of style or momentum.

Twins Smoke and Stack (both played, Parent Trap–style, by Michael B. Jordan, in peak form) return home to Mississippi after fighting in World War I and making their name in Chicago’s criminal underworld. With their earnings, they plan to open a juke joint: a sanctuary for Black joy, music, and freedom in the Jim Crow South.

Then, something strange happens.

Sinners turns.

What begins as a swaggering Southern period piece becomes something else entirely—part musical, part horror, part myth. Yes, there are vampires. But what’s scarier is that they may not be the real monsters.

Long before the supernatural enters the picture, Sinners reminds us why we go to the movies: to visit places we can’t otherwise. Coogler drops us into 1930s Mississippi so vividly that when you see catfish frying, you can practically smell the grease and taste the cornmeal. Like the popping juke joint it depicts, this world drips with texture and personality.

Grounding our journey is the music, which is soulful, stirring, and omnipresent. In Sinners, Black music becomes a living act of resistance—born from pain, but fueled by joy, defiance, and survival. Ludwig Göransson’s score is both epic and intimate, culminating in a magnificent sequence illustrating how the Delta blues laid the groundwork for generations of Black music (and popular American music) to come. It’s one of the most visually arresting and emotionally resonant scenes of any film I’ve seen in my life.

There’s also an epic eye-candy shot of Michael B. Jordan firing a Tommy gun in slow-motion, biceps bulging as he empties a clip into a clump of Klansmen.

If neither of these scenes brings you transcendent joy, you may be dead inside, like, you know, a vampire.

Speaking of that, Coogler, like Jordan Peele, deftly uses horror not just for thrills, but to tell a deeper story about America: one where Black culture is constantly drained, co-opted, or crushed for profit and control. Yet he avoids neat allegory or didactic symbolism. The supernatural and historical horrors on screen blur, reflecting and amplifying each other.

When the vampires first appeared, I expected an allegory of white culture preying on Black creativity. That layer exists—but it’s only one of many nuanced threads woven together.

To start, Remmick, the Irish vampire, isn’t a one-note villain. There’s a lingering sadness in his scenes—an old-world weariness that suggests he knows he’s become something he never meant to be. He’s both predator and pawn: a man whose history of displacement and marginalization has been weaponized to keep him above those who share his struggle. His hunger to belong is tragically relatable—and it helps us confront how assimilation is, by definition, a process of cultural consumption and quiet erasure.

By placing Remmick’s story alongside Smoke and Stack’s, Coogler invites us to consider how whiteness in America was constructed—and preserved—through separation. For immigrant groups like the Irish, being accepted as white often required aligning against Black Americans. Crucially, this contrast doesn’t flatten either experience. Instead, it expands our understanding of how race in America has been shaped by coercion, opportunism, and fear, as well as by resilience, solidarity, and survival.

Sinners also reminds us that white supremacy doesn’t need fangs to drain the life from Black communities. When Smoke and Stack’s juke joint opens as a beacon of Black joy, autonomy, and ambition, it’s swiftly targeted by the Klan, not because it’s merely a business or party spot—but because it represents something far more radical: Black self-determination. Like Tulsa’s Black Wall Street, it becomes a target the moment it begins to thrive. Coogler vividly illustrates how Black prosperity has always been perilous—either co-opted by cultural vampires like Elvis or crushed by racist backlash.

With this horrific backdrop, the ascent of Sammie, the blues singer at the center of this story, becomes moving and heroic. While his preacher father seeks salvation in church, Sammie finds it in music. The blues lets him leave Mississippi behind and build something new in Chicago.

Is all of this a lot to include in one movie? Yes.

Some viewers and critics found the genre shifts jarring and felt the film was trying to juggle too much. But to me, that’s part of its power. Sinners isn’t trying to be tidy. This movie doesn’t fit neatly into a box. The Black American experience doesn’t fit neatly into a box. This, I suspect, is the point.

Sinners is a distinctly American folktale. It’s unapologetically Black and fearlessly ambitious. Like the raucous nightclub it’s set in, it’s packed to the gills with creativity, personality, fun, and meaning.

Coogler’s gift as a director is that he doesn’t hand out homework in his films—he builds stories so rich that you want to stay after class just to talk about them. Sinners is a richly textured film that rewards both close reading and casual watching. Analytical viewers can chew on the subtext, while others can simply bask in the vibes, place, music, humor, and sensuality.

For example, people like me—you know, the kind who spend thousands of words pontificating about potatoes—are still ruminating on why that rendition of “The Rocky Road to Dublin” was so powerful yet so unsettling.

And that doesn’t even touch the nuanced portrayal of the Chinese American shopkeepers, who bridge the town’s white and Black worlds—a tender subplot worthy of its own essay, or Hailee Steinfeld’s Mary passing as white despite being mixed race.

What stuck with me was how evocatively Coogler reminds us that just as racial violence tends to repeat itself in cruelly predictable patterns, art and solidarity often follow in surprising, beautiful ways. The film’s Irish and Chinese American subplots hint at unlikely kinships forged through shared struggle—echoes of real-world moments like the Choctaw Nation’s 1847 donation to Irish famine relief. That gift, made by a people who had survived the Trail of Tears just 16 years earlier, reminds us: empathy, like music, travels far. It crosses borders, genres, and generations.

Sinners stirred up all of this and more for me—but you don’t have to share my interpretation, or think about any of it, to enjoy the ride.

Just sit back and listen to the music.

Invite some friends and spend a few hours in a place where headlines about tariffs and memes about the Pope can’t reach you.

As Sammie learns—good art won’t save the world—but it just might save your soul.

Great thoughts on a great movie. One additional theme I'm still rolling around in my head- how deeply the movie believes in spirituality and magic, and how clearly it does NOT in organized religion.

The shamanistic tradition in the music and Annie's hoodoo clearly have true power in this world- it is not until he takes off his protective amulet she made that repels both bullets and vampires that Smoke is physically harmed. But the church (and Catholicism in particular) do not- they're also in opposition to music, whereas the Vampires shrug off and even share in crosses and the Lord's Prayer. And that's a particularly clear choice when you're making a Vampire movie.

As you say, the themes blend, intentionally- vampires and white and Black people through music, spirituality through music, but institutional religion is one of the few things portrayed with no upside and no redeeming value.