“Language is the liquid that we’re all dissolved in, great for solving problems, after it creates a problem.” -Modest Mouse

“Flowers are only flowers because they fall.” -Lady Mariko

Looking sharp at the Met Gala

During my last visit to The Met, I spent an entire afternoon in the Arms and Armor exhibit. Much to the chagrin of Alexis and her friend, we didn’t see a single painting or statue. Instead we admired the craftsmanship of halberds, cuirasses, crossbows, and chainmail. Then I found the samurai section.

I spent a good hour just looking at razor sharp katanas with sharkskin handles. You may find this excessive. I’d counter that it’s easier to look away from Monet’s lilies than it is to look away from armor so iconic it inspired the design of Darth Vader.

Some men think about the Roman Empire daily. I prefer samurai armor.

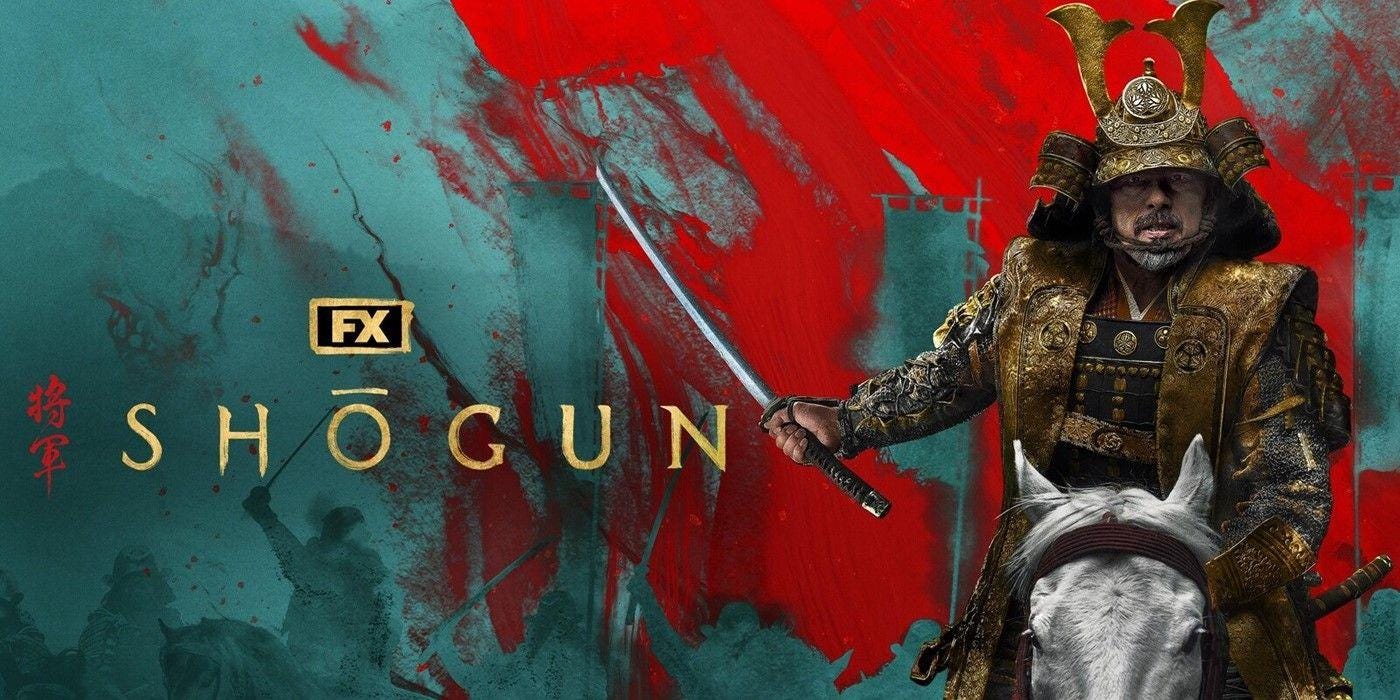

Once I learned that James Clavell’s Shogun was being made into a TV mini-series I knew who to text. Matt and Kevin are the type of friends that would have happily spent an afternoon in the Arms and Armor section of the Met with me. They share my giddy devotion to The Last Samurai. Somehow in our wildly different childhoods, we’d all contracted the same fever for Japanese warfare. Now, the only prescription was watching Shogun.

But what had we really signed up for?

Shogun is really about language

Shogun resembles many heavily hyped TV series. Like Westworld or Game of Thrones, it has an excellent cast and huge budget. It even has a vibey title sequence that’s so ornate you almost feel bad skipping it.

This is a carefully made, gorgeously visualized historical epic that commits fearlessly to the time period. This is evident in the costume, props, and set design, and especially in the treatment of language.

A distinct feature of Shogun is the dialogue, almost entirely in Japanese with English subtitles. This adds authenticity and places you in John Blackthorne’s shoes, a fish out of water Brit who guides you into the story.

Cosmo Jarvis plays Backthorne and also eerily resembles Tom Hardy. Hence our nicknames for him: Discount Tom Hardy, Tom Hardly, Kirkland Brand Tom Hardy, and so on.

The show is wise to limit this brand of bumbling Brits to one.

Blackthorne’s befuddlement is comical but useful, forcing viewers to consider the cultural clash from both sides. Like him, we struggle to justify the strict hierarchies and violent honor codes of the Japanese. Meanwhile, the Japanese characters observe just how vulgar, dirty, greedy, and violent Blackthorne and his Portuguese rivals are, making us laugh and nod in agreement.

Is the violence between Catholics and Protestants in Europe any more or less justifiable than the backstabbing between Japanese warlords? This is repeatedly gestured at but never resolved. Europe is tertiary in this tale. Japan is central. This is a good thing.

Blackthorne’s primary Japanese foil is lady Mariko, his translator. Navigating a hostile society that’s on the brink of war, Blackthorne relies on Mariko to forge alliances and stay alive.

As a story about geopolitical maneuvering and cultural exchanges, language, not swords or guns, is the most dangerous weapon on screen. This is most apparent in the scenes with Blackthorne. Shogun depicts the cross cultural moments that alternate between clumsy and heartbreaking, funny and precarious, serious and absurd. As Nerdwriter puts it in his video essay “How Shogun Makes Translation Exciting.”

“What’s made this new series so compelling to me is how it uses the act of translation to explore the possibilities and limitations of communication across cultures and communication, period.”

Through Mariko, we see how much language both embodies and shapes our cultural values. What we include, leave out, or just suggest with our word choice speaks volumes about our identity and point of view. As Nerdwriter puts it,

“The translation itself becomes significant, a mediation in the interplay of four minds. In trying to avoid conflict Mariko is faced with translating cultural values as well as language and that's not easy. When Blackthorne ask Buntaro for war stories he's communicating a positive English value for boasting that Buntaro considers vulgar and rude.”

Some of this show’s best scenes depic Mariko deftly navigating the linguistic dance between intent and implication to guide conversations away from danger. This surprisingly subtle show engages both text and subtext, often leaving you to connect the dots.

Shogun is really about duty

This linguistic game feels momentous because of the fatal consequences of every line of dialogue. Here death as the ultimate cost of being true to your word. Warlords expect their soldiers to give their lives in battle, and any breach of protocol may lead to ritual suicide. Every meeting, sake toast, and brothel visit has potentially deadly consequences.

Shogun depicts a time when Japan was divided between warlords, none with a legitimate claim to the throne. The interconnected alliances remind you of the messy start of World War One. People are beholden to each other, double-crossing, and maneuvering around each other constantly. The arrangement is untenable. The suspense keeps escalating.

While compelling, this 3D chess match of alliances and betrayals can be confusing at times. The characterization didn’t help. Besides the glorious gravitas of Hiroyuki Sanada as Toronaga, blathering Blackthorne and meticulous Mariko, I couldn’t keep all of the side characters straight, especially the scheming warlords. Maybe the subtitles were to blame. Thankfully, one character communicates primarily through epic sighs— I remembered him as Sir Sighs a Lot.

The last two episodes conclude in a “manners standoff,” where violence only occurs once enough protocol is breached. It’s a fascinating physical embodiment of the show’s themes. When the razor’s edge between words and implications becomes the literal blade of a sword, the characters must finally choose what truth to communicate through their actions.

Shogun is really about death

Shogun is a knife-point interrogation of morality and mortality. While death is ubiquitous, it is never glamorized. Epic fight scenes are scarce. There’s some stylish stabbing, but the swordplay defies Western expectations. Unlike The Last Samurai’s elaborate combat choreography, Shogun’s killings are brutal, short, and stoic. A sword is just a tool to achieve an outcome. This theme can be heavy-handed, using monologues as subtle as the earthquakes that preceded them to describe how Japan’s culture was built around impermanence and death. Yet, as Blackthorne shows, a musket ball kills just the same as a katana, so maybe finesse isn’t really everything.

Shogun is really about friendship

No, not onscreen. Beside’s Toronaga’s affection for his gorgeous falcon, I saw little affection between characters.

While the teaser trailers hinted at steamy scenes, the most intimate relationship most of the men in Shogun have is with a dagger shortly before it pierces their abdomen. Seriously, this is a show where ritual suicide happens so often you began to expect it after minor blunders. Left an insufficient tip for your Matcha Latte? Proceed straight to Seppuku.

The incessant violence drove me to haiku:

Bloody council rooms

Shock and dismay the Anjin

All mops are red here

Still, it was a killer excuse to see friends. Kevin’s fiancée Kaitlyn even joined us, disproving my theory that only boys would enjoy this much samurai drama. Over Japanese takeout, smoked chicken, and Drakes 1500s, we embarked on an historical adventure that took several months to complete. Sharing a tale this epic just felt right. Even the morbid rituals couldn’t kill our vibe.

Life got in the way at times. Sometimes we’d go weeks in between viewings, needing to watch the “Previously On” section attentively. Then we’d rehash the Machiavellian maneuvers we’d witnessed weeks ago. The gaps in our viewing made understanding the plot more difficult, but they also became part of the fun. By helping each other piece together the many intricately woven subplots, we began to understand the show and each other better.

Mariko may be right. The only constants in life are impermanence and death. Perhaps peace is just the fragile intermission between wars. We are all pawns except for Toronaga, and most of us are just as lost as Blackthorne.

If that’s true, we’ll need more shows like this. In such a noisy and confusing world, we need good translation and loyal allies now more than ever.