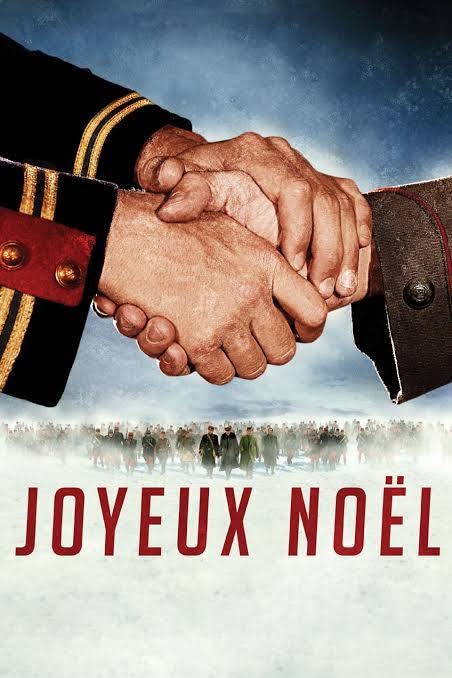

Oughts From the Aughts: Joyeux Noel (Merry Christmas) (2005)

My favorite underrated gems from the 2000s, explained in under 2010 words

A high school curriculum unfolds with the predictable, perfunctory rhythm of an advent calendar.

The mitochondria are the powerhouse of the cell. Odysseus saw the rosy fingers of dawn and Gatsby saw the green light. Long before Challengers, Ethan Frome showed us all that love triangles are tough sledding indeed. So, by sophomore year I knew with the certainty of Ethan Frome heading toward an Elm tree that it was time to learn about World War One.

World War Two has been so thoroughly covered by Hollywood and video games that young people rarely see it with fresh eyes. In contrast, World War One has received less attention because it’s harder to characterize, and nearly impossible to glamorize. Compared to its sequel, the stakes and sides aren’t as clean-cut, the morals are murkier, the purpose more vexing. So, after half a fall semester meandering the muddy trenches of the Western front, I was surprised and delighted to find a recently-released foreign language film to try to make sense of this particularly senseless war.

Joyeux Noel (Merry Christmas) is a historical drama about a strange and beautiful event: the Christmas Truce of 1914. During the first winter of World War One, troops on the Western front halted hostilities on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. Instead of killing each other, for a miraculous 24 hours, they exchanged carols, shared food and drink, and even played soccer in no-man’s-land. In a Hollywood landscape oversaturated with simplistic World War Two epics and saccharine Christmas movies, this is a surprisingly evocative Christmas movie that’s also about World War One.

However, the last time I saw this, I was 15, so I wasn’t sure how it would hold up on a re-watch. Watching Alexis writhe in discomfort during the opening battle reminded me just how harrowing this war is on screen. Trench warfare combines the mechanical efficiency of modern weapons with the archaic intimacy of close-quarters combat. Yet this bleak opening is necessary because it sets the tone and makes the spontaneous acts of empathy that follow much more moving.

The Christmas truce starts here, as it did in real life, with both sides exchanging Christmas carols across no-man’s-land, lobbing songs instead of shells at each other. The musical exchange that begins the fraternization is legitimately beautiful to watch. The Scots perform a rousing rendition of “I’m Dreaming of Home” on the bagpipes, and the Germans respond with “Silent Night.” Then, as the bagpipes play “Oh Come All Ye Faithful”a German tenor solist crosses no-man’s-land holding a Christmas tree with the audacity of Gal Gadot in Wonder Woman.

Stunned applause follows as heads poke above the parapet and the officers meet and agree on a ceasefire.

As the soldiers mingle cautiously and then enthusiastically, we see them exchanging whiskey, chocolate, and stories. Two of them bond over a trench cat that both the German and French lines have adopted as their own, beloved as Nestor by one side and Felix by the other. A Scottish medic, played to charming Glaswegian perfection by Gary Lewis, even leads the soldiers from three different nations in Christmas mass.

On Christmas day we see them bury their dead and then play a game of soccer. It turns out that, propaganda aside, they’re all Christian men who enjoy sports, songs, booze, and not being shelled.

What’s so effective about the tender middle act of this movie is the visualization of a simple question with revolutionary implications then and now:

What if we don’t need to be terrified of our fellow humans?

This makes the third act is as tragic as the second was hopeful. To spoil a century-old event, the truce doesn’t last. Not only do the soldiers have to return to shooting at each other, but when the commanding officers find out what’s happened they’re furious.

To the commanders, this beautiful act of fraternization is a dangerous threat that undermines the war’s premise and purpose. The Scottish, French, and German officers who let their troops fraternize during the Christmas true are all rebuked. This part of the third act is nearly as hard to watch as the intimate trench slaughter in the first act.

Hearing Lewis’s Father Palmer be chided for leading Germans in mass by his superior is particularly painful. The British priest who rebukes him uses Christian propaganda to demonize the Germans, employing dehumanizing language that even casual students of the intervening century’s history will find grimly familiar.

As punishment for their fraternization, the Germans are rotated off the front lines, sent to kill Russians on the Eastern front. As they’re shipped away we hear them humming “I’m dreaming of home,” which they learned from the bagpiping Scots across the trench. It’s a fitting and understated coda to the story.

The Christmas Truce is the rare real world example of what J.R.R. Tolkien would call a “eau-catastrophe,” a sudden positive outcome just when things look to be at their worst. When I first saw this movie in high school, it was this quality that drew me to it— showing the magic of Christmas briefly overcoming nationalism, xenophobia, and automated slaughter.

Re-watching it at 34 has a more sobering quality.

The reason the Christmas Truce has endured in history and popular culture is the piercing question at the heart of this film:

Is our default state one of fear and violence or one of curiosity and cooperation?

Which behavior is the real aberration?

Is it really strange that we briefly stopped mechanized murder 110 years ago to share songs and play sports or is it stranger how devoted we’ve since become to mechanized murder when we could have been sharing songs and playing sports instead? The power of Joyeux Noel is how it makes you reflect on how nationalism, xenophobia, and mass murder are just as artificial and culturally conditioned as Christmas. Killing people that speak a different language requires much more fiction and contrivance than just inviting them to share in dinner, prayer, and storytelling.

It’s equally sad and tender that this true historical even feels stranger than fiction over a century later. Cynical viewers of this film might wonder what type of movies they’ll make about Ukraine and Gaza in 110 years.

For me, this film was a reminder to look for the little joys, kindnesses, and miracles that are all around us, even on grey winter days. The world is often a bleak place, one that we’d all like a holiday from. Being brave in the face of this isn’t just about fighting the darkness; sometimes bravery is lighting candles and singing a song instead. To give up hope or empathy is to surrender key pieces of our humanity—the most fragile and important parts.